The Great Disenrollment: Examining Medicaid's Post-Pandemic Shift

The Medicaid unwinding process that began in April 2023 has significantly impacted healthcare access and coverage retention across the United States. The unwinding, triggered by the end of pandemic-era continuous enrollment provisions, led to substantial shifts in Medicaid enrollment and revealed both strengths and weaknesses in our healthcare system. The process disproportionately affected communities of color and highlighted the need for targeted policy interventions to maintain healthcare access for vulnerable groups, including people living with HIV (PLWH).

The Scope of Medicaid Unwinding

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act implemented the continuous enrollment provision in March 2020. This policy prohibited states from disenrolling Medicaid beneficiaries in exchange for enhanced federal funding, ensuring that people maintained health coverage during a time of unprecedented health and economic uncertainty. As a result, Medicaid enrollment surged from 71 million people in February 2020 to 94 million by April 2023, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) analysis.

The end of the continuous enrollment provision on March 31, 2023, initiated a complex process of eligibility redeterminations for all Medicaid enrollees—a task of immense scale and complexity. By the end of the unwinding period, over 25 million people had been disenrolled from Medicaid, while over 56 million had their coverage renewed, as reported by KFF. The overall disenrollment rate stood at 31%, with significant variation across states. For instance, Montana reported a 57% disenrollment rate, while North Carolina's rate remained below 20%.

Systemic Challenges in the Unwinding Process

One of the most concerning aspects of the unwinding process was the high rate of procedural disenrollments. Of those who lost coverage, 69% were disenrolled for procedural reasons, such as not returning renewal paperwork, rather than being determined ineligible. This suggested that many people who lost coverage may have still been eligible for Medicaid but faced significant challenges navigating the renewal process successfully.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) highlighted that administrative barriers contributed significantly to these procedural disenrollments. These barriers included:

Outdated Technology Systems: At least 11 states reported that their systems were old or difficult to use, making it challenging to produce real-time analytics essential for processing renewals effectively. This technological lag complicated efforts to implement necessary changes swiftly and efficiently.

Staffing Shortages: High turnover rates among eligibility workers led to vacancy rates reaching up to 20% in some states. Reports of low morale and burnout further affected the workforce's ability to handle the increased workload during the unwinding process.

Communication Barriers: States struggled to effectively engage people in the renewal process, particularly those facing language barriers. Non-English speakers often encountered longer wait times and struggled to reach assistance through call centers. These issues were compounded by a lack of robust state communication and engagement strategies.

Complex Paperwork: The renewal process often involved complicated forms and documentation requirements, which proved challenging for many enrollees to navigate, especially those with limited literacy or language skills.

Dr. Benjamin Sommers, a health policy expert at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, noted during the process, "The high rate of procedural disenrollments is particularly troubling. It indicates that we're not just seeing people leave Medicaid because they no longer qualify, but because they're struggling with the administrative hurdles of the renewal process."

These challenges led to frustration among enrollees and advocacy groups, highlighting the need for more streamlined and accessible renewal processes. The experience underscored the importance of investing in modernized eligibility systems, adequate staffing, and comprehensive communication strategies to ensure that eligible patients can maintain their coverage during future eligibility redeterminations.

National Enrollment Trends and State-Level Variations

Despite significant disenrollments during the unwinding process, Medicaid enrollment remained higher than pre-pandemic levels. As of May 2024, 81 million people were enrolled in Medicaid, an increase of about 10 million compared to pre-pandemic enrollment. However, this growth was not uniform across all populations. While adult enrollment remained over 20% above February 2020 levels, child enrollment was only about 5% higher.

Several factors influenced these disparities:

The pandemic's economic impact led to more adults becoming eligible for Medicaid due to job losses and income reductions.

States that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act saw more substantial increases in adult enrollment.

Children's enrollment remained relatively stable due to higher pre-pandemic enrollment rates and broader eligibility criteria through programs like the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

The impact of the unwinding process varied significantly across states, reflecting differences in policies, system capacities, and approaches. States that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act generally showed higher retention rates. Additionally, states that adopted strategies to streamline the renewal process, such as increasing ex parte (automated) renewals, saw better outcomes.

For example, Arizona, North Carolina, and Rhode Island achieved ex parte renewal rates exceeding 90%, while states like Pennsylvania and Texas had rates of 11% or less. These differences underscored the importance of state-level policies and systems in determining unwinding outcomes.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reported that states with higher ex parte renewal rates tended to have modernized eligibility systems that could effectively leverage data from other programs to confirm eligibility. This reduced the administrative burden on patients and helped maintain continuous coverage.

These variations highlighted the critical role of state-level decision-making and infrastructure in shaping Medicaid enrollment outcomes during and after the unwinding process. They also pointed to potential best practices for maintaining coverage and streamlining enrollment processes in the future.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Medicaid Disenrollment

A particularly concerning aspect of the unwinding process is its disproportionate impact on communities of color. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), more than half of the people who lost coverage were people of color. This disparity is exacerbated by existing barriers to healthcare access. The SPLC notes that communities of color face more barriers to healthcare access, such as limited internet, transportation, and inflexible job schedules.

The impact is particularly severe in states that have not expanded Medicaid. The SPLC report highlights that "residents from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi make up over 40% of the adults in the coverage gap nationwide. People of color make up about 60% of the coverage gap nationwide."

The Human Impact of Coverage Loss

The impact of coverage loss extends beyond statistics. Personal stories highlight the real-world consequences of the unwinding process. Justin Gibbs, a 53-year-old from Ohio, had to go without blood pressure medication for a week after losing his Medicaid coverage in December, according to CNN. Such disruptions in care can have serious health implications, particularly for people managing chronic conditions.

A KFF survey reveals the broader health impacts of coverage loss. Among those who became uninsured after losing Medicaid:

75% reported worrying about their physical health

60% worried about their mental health

56% said they skipped or delayed getting needed health care services or prescription medications

Impact on HIV Care and Policy Implications

The Medicaid unwinding process also highlighted significant challenges in maintaining healthcare access for people living with HIV (PLWH). While specific data on Medicaid disenrollment among PLWH during the unwinding were limited, general trends among vulnerable populations indicated potential risks. A KFF report found that many of those who lost Medicaid coverage experienced increased out-of-pocket costs, interruptions in medication adherence, and deteriorating health outcomes. These challenges were particularly critical for PLWH, for whom continuous access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is essential.

Key considerations for PLWH during the unwinding process included:

Continuity of ART: Ensuring uninterrupted access to antiretroviral medications is mandatory for maintaining viral suppression and overall health.

Role of Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: This program played a critical role in filling coverage gaps, but it's not a substitute for comprehensive health insurance.

Targeted Outreach: Community-based organizations and AIDS Service Organizations (ASOs) were essential in providing specialized support and enrollment assistance to PLWH.

Data Collection: Improving data collection on Medicaid disenrollment rates among PLWH can inform targeted interventions and policy adjustments.

The unwinding process underscored the need for policies that safeguard continuous healthcare access for PLWH. Implementing strategies that address these specific needs can help prevent coverage disruptions and improve overall health outcomes for people living with HIV.

Economic Implications of the Unwinding Process

The Medicaid unwinding process had significant economic implications for patients, healthcare providers, and states. For people who lost Medicaid coverage, the consequences often included financial instability and increased medical debt. A study by the Urban Institute found that adults who experienced a gap in Medicaid coverage were more likely to report problems paying medical bills and to have medical debt.

Healthcare providers, particularly safety-net hospitals and community health centers, faced increased rates of uncompensated care as a result of the unwinding process. This strained their financial resources and potentially affected their ability to provide care to their communities. The Commonwealth Fund noted that increased uninsured rates could lead to higher healthcare costs in the long term due to delayed care and increased emergency room visits.

For states, the unwinding process presented complex economic challenges. As the enhanced federal matching rate provided during the pandemic phased out, many states grappled with increased administrative costs associated with the unwinding process. A report from the Brookings Institution highlighted that states faced a complex set of trade-offs as they navigated the unwinding process, balancing the need to control Medicaid spending with the imperative to maintain access to care for vulnerable populations.

The full economic impact of the unwinding process continues to unfold, with ongoing implications for state budgets, healthcare provider finances, and patient economic well-being. These insights will be important in shaping future Medicaid policies and developing strategies to mitigate economic challenges associated with coverage transitions.

Policy Recommendations and Best Practices

To address these challenges, several key strategies have been identified:

Streamlining Renewal Processes: Increasing ex parte (automated) renewal rates can reduce the burden on people and minimize procedural disenrollments. For instance, Louisiana achieved a 49% ex parte renewal rate by leveraging data from other public benefit programs and improving data matching processes.

Targeted Outreach: Conducting outreach to vulnerable populations, including communities of color and people with chronic conditions, can help reduce disenrollments. The Ohio Department of Medicaid partnered with community-based organizations for door-to-door outreach in areas with high procedural disenrollments.

Implementing Continuous Eligibility: Policies that provide 12-month continuous eligibility can stabilize coverage and reduce churn. Oregon implemented a two-year continuous eligibility policy for children under six.

Enhanced Federal Oversight: Strengthening monitoring and enforcement of federal requirements ensures state compliance. CMS should leverage new authorities to require corrective action plans from states with high procedural disenrollments.

Improving Data Collection: Robust data collection and timely reporting enable quick identification of problems. States should report disaggregated data on disenrollments by race, ethnicity, and other demographics to address disparities.

Leveraging Technology: Modernizing eligibility systems improves accuracy and efficiency. Implementing text messaging, email communication, and mobile-friendly online portals helps people update information and complete renewals more easily.

Expanding Presumptive Eligibility: Allowing qualified entities to make preliminary eligibility determinations provides temporary coverage while full applications are processed, ensuring continuous access to care.

Addressing Systemic Inequities and Long-Term Solutions

The unwinding process exposed systemic inequities within the healthcare system, particularly affecting communities of color and rural areas. Long-term solutions include:

Investing in Underserved Communities: Enhancing access to healthcare services in marginalized areas.

Improving Health Literacy: Providing education to help people understand their health coverage options and navigate the system.

Strengthening Social Safety Nets: Expanding programs that address social determinants of health, such as housing, nutrition, and transportation.

Without significant policy interventions, coverage losses could lead to worse health outcomes and increased disparities, as emphasized by the Urban Institute.

Conclusion

The Medicaid unwinding process revealed both challenges and opportunities in our healthcare system. It highlighted the need for more efficient, equitable, and resilient approaches to health coverage. Key lessons include the importance of streamlined processes, targeted outreach, and robust oversight.

Moving forward, policymakers, healthcare providers, and advocates must work together to implement solutions that ensure continuous, accessible care for all, especially vulnerable populations. This effort is not just about health policy—it's a matter of equity and human rights.

As we continue to navigate the evolving healthcare landscape, our goal should be to build a system that provides stable, continuous coverage and leaves no one behind. This commitment is essential for improving health outcomes, reducing disparities, and strengthening our nation's overall health infrastructure.

Patient Care Suffers at the Intersection of Nursing Shortages and Hospital Consolidation

Last week, New York City nurses at Mount Sinai and Montefiore hospitals went on strike for about three days before the hospitals reached a tentative agreement, bringing nursing staff back to work immediately. The New York State Nurses Association, which organized the strike, lead an incredible media campaign around the strike effort, warning communities (and hospitals) well ahead of the strike about the need for good faith negotiation and changes weren’t just about ensuring nursing staff compensation kept up with inflation, but primarily based on working environments and patient safety, with key demands around improving staff to patient ratios. The campaign was so successful, four other hospitals which would have been subject to the strike reached agreements ahead of the Monday deadline. While the American Nurses Association did not have a direct hand in the strike, they supported the move by the New York State Nurses Association, stating the need indicates a “systemic breakdown” regarding safe staffing levels, protecting nurses from workplace violence, and supporting nurses’ mental health and well-being, among other challenges.

That idea offered by the American Nurses Association isn’t wrong – this issue is systemic. Lats month, the New York Times outlined how Ascension, one of the nation’s largest hospital systems, had neglected staffing needs for years, leading to hospital locations across the country being ill-prepared for the demands and challenges COVID-19 brought. The piece, entitled How a Sprawling Hospital Chain Ignited Its Own Staffing Crisis, details how Ascension bragged about reducing its labor costs and reducing its number of employees per occupied bed. But this, in combination with other factors like health care workers becoming sick, left Ascension hospitals in a near unimaginably bad position to handle waves of COVID-19 patients. Indeed, the New York Time also ran a piece in August of 2021, highlighting the plight of nurses struggling to keep up with demand of the “Delta variant wave”. The beds were there, the staff to ensure those beds could be safely occupied were not. On top of already having poor staffing to patient ratios and many staff falling ill with COVID-19, thousands of health care workers died in these “crisis” waves. Several times throughout various COVID-19 “waves”, hospitals advertised their need for nursing talent and offered to pay exceptionally well for those traveling nurses who could help meet the immediate demands of the moment. Already retained nurses were not necessarily offered similar compensation as their traveling counterparts, even if some hospitals did end up offering supplemental pay. Largely, those supplemental payments have dropped off as CARES Act dollars have dried up.

Put yourself in the nurse’s position, for a moment. If you could get paid say… three months’ worth of salary working two weeks away from home by traveling, would you do it? Consider now, there is no end in sight for the demand in traveling nurses. You can find work whenever you want and it’s well-paid enough that you don’t have to worry things like negotiating to compensate for inflation. And if the area you’re working is experiencing workplace safety issues or violence from patients who have bought into conspiracy theories that you and your colleagues are somehow making up a respiratory pandemic, you can just leave. More and more nurses weighed this position and more and more nurses opted to travel. This has had likely one of the most significant drivers of hospital labor costs increasing by at least 37% since 2019. And hospitals, for their part, aren’t necessarily cutting out activities like buying up other entities or executive compensation in order to reinvest in their staff, rather, they’re billing insurance companies more. That increase in cost of care also translates to an increase in insurance premiums for consumers and other plan changes that might adversely affect patients and patients’ ability to afford care. For example, Health System Tracker, a project of Peterson Center on Healthcare and Kaiser Family Foundation, detail how the Affordable Care Act’s maximum out of pocket limit is growing faster than wages and how emergency department visits are now exceeding affordability thresholds for many consumers with private insurance.

These systemic changes need to be addressed immediately by state and federal policymakers. Unions alone cannot stop hospital consolidation and can only leverage so much to ensure appropriate staffing levels without risking the quality of care patients receive in any given community.

Because of the greed that drives hospital consolidation, the “rural hospital crisis” is coming to an urban area near you. An example of the emergency nature of this situation can be found in Atlanta Medical Center’s sudden closure, an issue Louisiana Children’s Medical Center’s purchase of Tulane hospitals from HCA Health could replicate in another majority Black city.

Given the billions of dollars hospitals have received in CARES Act dollars and continue to receive in 340B dollars, regulators need to slam on the breaks of approving hospital consolidation purchases. Communities and their elected officials should also critically ask hospital executives (and investigate a factual answer, not a public affairs answer), “Are you really operating as a health care provider or are you operating as a real estate entity and buying out all of your competition at the expense of our communities?” Indeed, the real question that’s going to drive some much, much needed oversight on hospitals would be, “Are you using these dollars meant for public benefit to buy out your competition?”

It's high time hospitals be held accountable.

Advocates Gather to Discuss Pressing Healthcare Issues

The ADAP Advocacy Association held its second Fireside Chat retreat this year, assembling in Chicago to discuss a broad range of issues. The Fireside Chats are somewhat coveted for the nature of the space they provide, with representation of a variety of industry partners, advocacy and service organizations, and patient advocates who don’t necessarily hold any particular affiliations. CEO, Brandon M. Macsata, refers to the gathering as “a group therapy session” whereby the richness of the advocacy work is most frequently the result of conversations at the Fireside Chat, but not necessarily rooted in seeking specific solutions confined to the four walls of the meeting room. The meeting format frees attendees from needing to be the “problem solvers” and allows for a free flow of ideas and perspectives collaboratively that might not otherwise arise. Topics for this event included combatting counterfeit medications, reforming the 340B Discount Drug Program, and dissecting COVID-19’s impact on public health programs.

While many of the participants were familiar with the notion of counterfeit medications, few were necessarily familiar with the details of safeguards taken to ensure patients are indeed receiving the medications they expect to receive or how large recent instances of counterfeit HIV medications were possible. Shabbir Imber Safdar from the Partnership for Safe Medicines started the conversation by sharing the status of implementation of the Drug Quality and Security Act, and how packaging was sold and resold with fake product in containers as part of one of the counterfeit schemes in Florida. Participants asked about various aspects of enforcement and implementation, drivers of fake medicines and medication supplies, to learn that enforcement largely falls outside of criminal codes and to civil litigation on fraud, pushed by medication manufacturers – a cost not well appreciated when put under the lens of medication costs. Advocates also considered more overt impacts of counterfeit medications in the opioid crisis and how they might need to approach community education on the issue of counterfeits in order to further medical mistrust.

The 340B discussion proved to be particularly lively. While having to segregate the pointed and necessary reminder that much of public health program funding is largely dependent on 340B revenues because Congress refuses to adequately fund public health programs, within minutes, participants began asking where patients fell in the funding scheme. Issues of charity care as a measure of success of the program (and the fact that hospital charity care has fallen dramatically since the passage of the Affordable Care Act), the ever-expanding role of contract pharmacies, and how federal grantees are being “caught in the middle” were frequently mentioned. As advocates asked questions, one participant rightly and repeatedly reminded the audience “there are no requirements as to how those dollars are spent.” One participant asked pointedly, as the usual “sides” of the 340B debate began to settle in, “will you come to the table with those perspectives you disagree with to find solutions?”

The final discussion of the Fireside Chat returned to COVID-19’s impact on public health programs. Once again, yours truly facilitated the discussion, though this time it was less on policy issues and more on the state of patient advocacy and provider services as a response. With concentration on sustainability and succession planning, participants reflected how the crisis phase of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted not just the weaknesses in public health programs, but also re-emphasized the need for HIV advocacy to consider appropriate succession planning and mentorship, as much as our service organization partners need to find room in their budgets to hire enough staff to not burn out their existing staff. Reminding the audience, I reflected, “Because eventually Bill Arnold dies.” The statement hit home for the room’s audience, referring to the empty seat draped in the fishing vest with the AIDS red ribbon on the lapel once worn by the Lion of HIV/AIDS advocacy. We have to plan better and we have to be willing to make these investments now, not later. I implored funders in the room to consider how they might incentivize funded organizations to begin succession planning and mentor investments.

After two years of most, if not all, in-person patient advocacy events being suspended, it was refreshing to convene with such a diverse group of public health stakeholders in Chicago. The ADAP Advocacy Association’s Fireside Chat retreats have filled a void in the patient advocacy space by the very nature of their uniqueness, and CANN remains committed to seeing them succeed. Chicago, like the one earlier this year in Wilmington, did just that.

ADAP Advocacy Association Resumes Fireside Chat Retreats

The Community Access National Network (CANN) celebrated the return of ADAP Advocacy Association’s (aaa+) “Fireside Chat” retreats after a two and a half years pause, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. CANN has regularly participated in the Fireside Chats since their inception and enjoys a robust partnership with our sister organization aaa+. The event, held in Wilmington, NC, featured 23 stakeholders, including patients, advocates, and manufacturer representatives and discussed the issues of “utilization management”, the status of Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) plans and activities in the South, and the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on public health.

Recognizing current COVID-19 transmission and community level trends, aaa+ developed a robust self-administered testing protocol, wherein participants tested prior to travel, upon arrival, and after returning to their home areas. aaa+ provided rapid self-test kits to each of the attendees. The idea here is important to note, in part, because a chain of transmission was indeed interrupted when one planned attendee reported a reactive test result from their test upon arrival, despite having had a nonreactive test result from their pre-travel test the day before. As a result, the person affected did not actually attend any sessions and appropriately self-isolated. Other attendees expressed gratitude for the reduction of risk, respect of their health and the health of attendee household members, and wished the person affected a speedy recovery. Truly, gathering safely can be done and done well, as demonstrated by aaa+’s efforts here.

Prevention Access Campaign’s United States Executive Director, Murray Penner, presented the issue of payer “utilization management” affecting people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA), with respect to broad issues of health care and specific to AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs). Opening commentary reminded the audience that utilization management practices affecting health other than HIV also affects access to care for PLWHA and, in some cases, where care or coverage is denied may also result in a patient disengaging from their HIV-specific care. Conversation also discussed utilization management affecting access to pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV (PrEP), in the context of generic antiretroviral (ARV) products, barriers to accessing new products, as a benefit of reducing unnecessary medical tests and preventing contraindicated care. Patients and advocates readily shared how utilization management being a barrier to care is not an “outlier” situation in which patients being denied medically necessary care only occurs in “rare” occasions, rather this is a frequent occurrence with these payer practices routinely and regularly require additional administrative burdens to be met and sometimes requiring circumstances contraindicated by the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approved indications for products or services. Advocates pushed back against the idea “you just want the latest drug like you want the latest iPhone” by emphasizing how the fight against HIV will not be won by having disparities in access maintained along lines of who can afford the most “elite” health care plans. Discussing how advocates can leverage state planning bodies and the role public payers could play in directing managed care organizations to reduce barriers to care as presented under utilization management practices, attendees envisioned robust yet protective access to care aimed at addressing issues of health equity and the critical role of payers in Ending the HIV Epidemic. Attendees also suggested evaluating utilization management practices under a lens of the Affordable Care Act’s rules against “discriminatory plan design”.

A lovely networking lunch followed the first discussion and attendees got the chance to bond with others they had yet to meet or reconnect with those they haven’t seen in a while. Honestly, the amount of respect and joy had during the lunch filled the room, with discussion of other areas of interest and even raucous laughter could be heard from the hallway. The energy generated from the first discussion was readily palpable.

The second discussion, lead by Community Education Group’s Director of Regional and National Policy, Lee Storrow, lead the second discussion on the status of Ending the HIV Epidemic in the South. In providing context for the update, advocates discussed their hopes and expectations when EHE had been announced under the Trump administration. While much energy had been generated, and that in and of itself is exceptionally valuable in the context of the 40-year fight against HIV, the “significant resources” advocates expected have not materialized and the addition of yet another plan has further complicated already layered reporting burdens for service providers funded under Ryan White and other HIV related initiatives and governmental funding streams. One attendee remarked “we’ve been doing the same thing for 30 years and the last 10 haven’t progressed, it’s time to do something different.” As a response, discussion moved to develop planning and programming to include the lens of “economic empowerment” of PLWHA by way of employment opportunities generated from these programs being targeted to recruiting staff from affected patient populations and served zip codes. Another attendee discussed how such an opportunity elevated her own professional experience and helped ensure her program better reflected the demographics of affected communities – ensuring better engagement and more effective outreach in her area. Attendees discussed the idea behind EHE as a “moon shot” but really seems to be hindered by the lack of cohesive systems communication across public health programs, in particular with data sharing between Medicaid and Ryan White funded programs in various states. This highlighted opportunities and barriers, manifesting in strategic planning on what cohesive data sharing might look like in an ideal. The session ended with conversation regarding “gatekeeping” among certain advocate circles when it comes to accessing institutional and governmental power and a certain lack of transparency as to exact “who” decision makers are due to bureaucratic processes, with the final note being “where is the red tape and who has scissors?”

The first day of planned discussion was capped with a dinner in which attendees continued to share with one another personal and professional details and ideas, making plans to socialize, discussing advocacy development opportunities, upcoming concerns regarding court ruling, legislation, and regulation, and programmatic planning within each other’s specific entities. The theme being “how can we help each other succeed?”

The second day of discussion held the final topic, COVID-19 impacts on public health, facilitated by CANN’s chief executive officer, Jen Laws (me). I opened the conversation by sharing the goal of the conversation being to “define” the impacts of COVID-19 on public health infrastructure and programs. Attendees were asked to share one “good” thing to come out of our collective response to the cOVID-19 pandemic and one “bad” thing (or “something we would like to go away”). Many attendees celebrated the innovation of flexibilities offered by various temporary governmental regulation and the “forced modernization” of health care in many situations – namely, telehealth. These flexibilities, including the continuous coverage requirement for Medicaid programs under the public health emergency declaration, are threatened to end as the public health emergency winds down and advocates attend the Fireside Chat expressed a certain foreboding of returning to “normal”. Specific highlights were given to the downside of relying on telehealth, especially for rural communities lacking the necessary infrastructure to make health care accessible – particularly in hospital deserts. Attendees reflected on the data “blindness” of the current moment, noting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) 2020 HIV surveillance report lack of completeness compared to previous years. “Bill Arnold reminded me frequently that the AIDS crisis is still just around the corner. We can’t blink,” I shared with the group to many nods as concerns for patients who dropped out of care weighed on the moment. Moving the discussion forward, attendees identified methods of advocate development and influencing state and federal power by more readily engaging manufacturers in their efforts to prioritize patient voices and experiences. The necessity to recognize the state of advocacy as needing re-development and investment was apparent and the note the event ended on, as attendees reflected the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the public health and advocacy workforce.

While much discussion was had throughout the Fireside Chat, much more was committed to following the event. As with many in-person events, as opposed to virtual events, the quality of the experience was not absent on anyone there. It felt good to be in the physical presence of one another. We sought and gained inspiration and enthusiasm and we do so with clear cognizance of COVID-19 as a risk. If advocates and our partners can continue to similar efforts that both keep us safe and connected, the future (not without its challenges) is bright, equity-focused, empathic, and patient-driven.

Misinformation: An Ever-Growing Public Health Threat

Author’s note: For good reasons, the terms “misinformation” (those ideas which are slightly distorted) and “disinformation” (ideas which are contrary or contradictory to actual fact) are distinct. However, for the purposes of public messaging, these terms are often interchangeable so as to not collide with natural defense mechanisms of an audience. Similarly, for this blog, the terms will be used interchangeably.

There’s no two ways about the issue of health misinformation – politely, a term to describe conspiracy theories which range from moderately frustrating and lacking factual evidence to downright deadly. On the issue of public health measures and mutual community investment into one another’s health outcomes, the issue grows exorbitantly.

Before we move forward – the issue of gun violence is both a public health issue and a humanitarian one. Like abortion and gender affirming care, the issue of gun violence is not an area of expertise I possess and the analyses provided in these blogs are specific to policies and programs affecting HIV, HCV, and substance misuse. However, we cannot move on without directly addressing the role misinformation is playing right now as families grieve the loss of their children as a result of another school shooting. Within mere hours after the shooting made national news and before even the full count of children murdered had yet become clear, misinformation, driven by conspiracy and bias regarding the shooter’s identity was already proliferating across social media. Indeed, the idea which falsely linked multiple transgender women to the shooting was touted by Representative Paul Gosar. These actions have already resulted in a trans woman being assaulted in Texas.

This isn’t new. The problem of misinformation around COVID-19 had already grown so significant by the time President Biden named a Surgeon General, one of Dr. Vivek Murthy’s first acts as Surgeon general for this administration was to issue an advisory warning of the personal and public health dangers of misinformation. In addition to the issue brief accompanying the advisory, the Surgeon General’s office now maintains an information page for various stakeholders, including individuals. Yet and still, even two years into this pandemic, where incredible feats of science – like producing a viable vaccine within twelve months of an initial outbreak – have occurred, people so well-regarded as to be elected to federal and state offices are either outright shouting flagrant falsehoods or calmly suggesting COVID-19 vaccines cause AIDS, like Senator Ron Johnson did earlier this month. The seed of doubt and big bad scary things are the things of nightmares and in the absence of easy to access, easy to understand, and static answers, there are people willing to consider these nonsensical leaps as valid possibilities.

None of this is new for folks navigating HIV misinformation or stigma. The problem of misinformation around HIV isn’t some far off issue that we don’t need to concern ourselves with domestically, indeed it thrives today in the backyards of “every day Americans”. The most pernicious idea being “HIV is over” seconded only by the moralizing ideas around “who” gets HIV – that such a diagnosis is somehow a justified punishment from “God” rather than the end result of a negligent society so infected with layered biases as to not acknowledge that racism (not race), misogyny, homophobia, ablism, and every other moral and ethical rot has driven those most in need to also be those most at risk. Hate and misinformation so often leaves “disproportionately impacted communities” so “vulnerable” the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a whole segment of their website and millions of dollars in programming aimed at reducing HIV stigma.

Part of the issue lies with a lack of digital literacy, an undying effort for fragile egos to leverage fear and their own ignorance for pitiful power grabs, and a near tangible disgust lobbed in response to casual conversation going just a bit sideways – tribalism at its best, as it were. Misinformation and conspiracy theories thrive when people are afraid and looking for answers that are easy to grasp and never change and the idea that things would never change once investigated is, at its roots, anti-science. The nature of science is to explore and challenge assumptions, test theories, and change our ideas based on the results. Regardless of what one thinks of themselves, reading an article about a study or even ten articles about a dozen studies isn’t “research” – it’s not even a literature review – and the fact that we as a society cannot come to agree on what defines a “fact” or “research” or release a desire to exclaim “expertise” in an effort to save an ego is deadly.

I’m a giant fan of librarians, the last great defenders of knowledge at every turn in history, and the attacks on their profession are as dangerous, in general, as they are to public health, in specific. Ultimately, librarians are the ones who end up teaching us how to navigate conflicting information and maintain the humility that is necessary to fight this moment – no question is dumb, asking for help is a super power, and being able to admit when you’re wrong is next to Godliness.

As state capitols across the country grapple with the likes of Robert Kennedy Jr. showing up exploit people’s fears, it is the duty of advocates across all issues to urge our political leaders to not indulge in conspiracy and misinformation, to show some kindness to our audiences who are coming from a very reasonable sense of being afraid of what it might mean if COVID-19 really is with us forever, and work to find that common ground we all proclaim to fight for:

We all want the same things for ourselves and our families; a safe place to call home, a good job that pays the bills, and a sense of happiness and peace. In the meantime, those with the power to influence policy also need to be advocating for meaningful funding in both public health and public education.

Community Roundtable Defines the Shape of Public Health Advocacy Amid COVID-19

Last week, Community Access National Network (CANN) hosted its annual Community Roundtable event, like last year, focused on the impacts of COVID-19 on public health programs and patient advocacy around HIV, viral hepatitis, and substance use disorder. CANN’s President & CEO (your’s truly) was joined by Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF) Director of LGBTQ Policy, Lindsey Dawson, and Georgetown University’s Katie Keith. Attendees included representatives from patient advocacy organizations, state and local health departments, clinical laboratories, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and federally or state funded service providers. The virtual event was sponsored by ADAP Advocacy Association, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare.

I welcomed attendees, noting my own professional admiration for both Lindsey and Katie, as experts leading in education on policy issues and data analysis around issues affecting communities highly impacted by HIV, viral hepatitis, and substance use disorder. Prior to co-presenters introducing themselves, audience members were reminded both KFF and Georgetown University are both non-partisan, education entities. The impetus and aims of this year’s event in including these astounding co-presenters was to help define the ecosystem of public health affecting programs particularly serving patient communities CANN serves.

Lindsey’s presentation offered a “potpourri” of relevant data regarding AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and Ryan White Funding stagnating, tele-PrEP, the federal Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative, Medicaid programs, and LGBTQ people’s health outcomes (especially mental health) throughout the pandemic thus far. Reviewing previously published KFF data and briefs, Lindsey reminded attendees that federal appropriations for HIV programs have largely stagnated for more than a decade and, when adjusted for inflation, have fallen. Despite the federal EHE initiative, seeking to jump start the country’s stagnating HIV progress, does not meet the funding requests of advocates. Large doubt remains as to exactly how much can be done with how little has yet to be given. For good reason, the audience was asked to consider if the existing roadmap is the “right” roadmap and what EHE might need to look like in the coming years in order to meet the goals of the initiative. Lindsey reminded attendees that 36% of PLWH live in Medicaid non-expansion states, including Georgia (which just last week shut down a proposal to expand the state’s Medicaid program to PLWH under a waiver). Moving onto a particular point with regard to access to care, tele-PrEP program successes (and weaknesses) could be attributed to flexibilities which have been the direct result of early policy answers to COVID-19. These flexibilities are among policies patient and provider communities stand to lose when the public health emergency comes to an end, unless legislators take action. Wrapping up her presentation, Lindsey drew attention to the health outcomes affecting a highly impacted patient population, LGBTQ people. Data from KFF showed LGBTQ people were more likely have received a COVID-19 vaccination series, more likely to consider COVID-19 vaccination a duty to community and others in an effort to help keep healthy, and more likely to have experienced negative mental health outcomes as a result of the pandemic.

I followed Lindsey’s presentation discussing the landscape of patient advocacy in the age of COVID. Recognizing COVID-19, despite any sentiment of the public at large, is not “over”. Considerations regarding in-person attendance to events, meetings, and travel are still in flex. Also recognizing the political landscape has significantly soured relative to “public health” in general, even if not to HIV, viral hepatitis, and substance use programs specifically, and that dramatically impacts both court rulings and legislators’ willingness to consider the crucial role “legacy” public health programs play in maintaining the health of the nation. Cautioning against potential neglect, rather than support (so much for the “heroes” of the early epidemic), I reminded audiences of the power of in-person events and the need to weigh precautions and monitoring of COVID transmission metrics when planning in-person events, regardless of how big or small they may be. Further on, the presentation focused on the structure of effective advocacy via storytelling, personalizing experiences, providing supporting data to make those personal experiences tangible among a constituency, defining an “ask” by knowing the mechanisms of action (re: actionable policy), and readily recognizing the powers, humanity, and limits of an advocate’s audience.

The final presentations, provided by, Katie Keith, reviewed historical and anticipated policy changes, including those relative to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – specifically, the family glitch and section 1557 – and those as a result of early COVID-19 legislation, much of which is quickly coming to the end of their legislatively defined program periods, either by specified date or by way of ending the federally declared public health emergency. Katie reviewed how the Biden administration approached some of these issues upon transition to power, having already met 8 of the policy requests of advocates, have yet to meet 4 of those requests, and at least 1 request was “in progress” with potential for administrative resolution any day now (section 1557 final rule re-write, specifically defining the edges of the ACA’s non-discrimination protections. Katie also briefly discussed how the Dobbs (abortion) ruling may impact domestic public health programs, urged attendees to watch Kelley v. Becerra, and urged advocates to closely watch the 2022 midterm elections as legislators have an unbridled ability to impact public health programs.

Panelists wrapped up by reminding attendees they and their organizations remain a readily available resource. The slide deck can be downloaded here.

Sadly Predictable: STIs & HCV Rates Rising Again

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently shared data showing a rise in most sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in 2020, despite a reduction in screening due to the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting public health programs aimed at STIs screening and treatment. While the statement focused on syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, Hepatitis C and HIV can also be transmitted via sexual contact. Dr. Juno Mermin, the CDC’s Director of the National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, blames some of the issue on a historical lack of investment in public health and stigma.

While Dr. Mermin’s sentiments are well appreciated, the potential for a developing “blind spot” as a result of COVID-19 diverting already scarce resources serving these programs in order to address COVID-19, including human resources (disease investigation specialists – DIS – to be specific), was well-noted and should not be considered to be well-understood as of 2022. Public health surveillance and other aspects of infectious disease monitoring have been direly harmed by the diversion of these brain and labor trusts as opposed to a national effort to strengthen these amid a compounded public health emergency. Indeed, we’re just now beginning to assess the potential damage caused by COVID-related disruptions in pre-existing public health programs, specifically those designed to address STIs. And while we’re doing all of this effort to better understand what’s happened, we’re at risk of state legislators underappreciating the necessity of the moment as politically driven distaste for public health programming is resulting in states considering massive cuts to their health departments (ie. Louisiana’s House just passed a budget gutting the health department by $62 million, despite the agency struggling to recruit and retain talent due to years of disinvestment – and Louisiana isn’t alone).

The disease burden of these rising infections falls most heavily among Black communities and young people, with a special note to be given to the incredible rise of congenital syphilis infections, especially among impoverished pregnant people struggling with access to care. Dr. Mermin has emphasized a need to invest in both public health programs and prophylactic vaccines to prevent the bacterial infections. To be clear, when we talk about public health investments, we mean:

funding increases so that public programs can compete with private industry for labor and talent recruitment and retention;

infrastructure increase so that health departments and their funded service contractors and grant subrecipients can afford things like modernized software, functioning computers, and integrated data systems that aren’t reliant on fax machines;

flexibilities and appropriate funding for support services, especially those designed to address housing needs of served communities;

federal funding leveraged to increase linkage and retention in care services (including transportation to medication retrieval as well as medical service visits); and

federal funding incentivizing stigma and bias reduction in medical and service providers who are also grant recipients and subrecipients.

In addition to public investments, private investments are long overdue in terms of antibiotic treatment developments, especially with regard to multidrug resistant STI-causing bacterium. The last time a truly novel antibiotic was developed was 35 years ago in 1987 and the [pipeline isn’t looking particularly promising. The lack of investment in developing more effective and new antibiotics is so stark, Pew just kinda gave up on tracking it in December 2021.

Beyond access to care and treatment, education regarding STIs has been under attack for…well…as long as any of us can remember and 2022 has found politicians claiming this kind of education, when presented comprehensively, might be considered “grooming” children (referring to psychological training of vulnerable people to make them more compliant with being sexually exploited and assaulted). Despite thirty years of research showing comprehensive sex education reduces the incidence of STIs among youth and well into adulthood politicians continue their assault on public by making particularly disingenuous claims regarding the nature of sex education n publicly funded schools. Let me back that up, these folks are outright lying in order to leverage fear, ignorance, and already existing social tensions to exploit and marginalize already vulnerable populations.

The unfortunate nature of public health, especially for those who had zero knowledge of public health prior to COVID-19 screaming onto the scene, is the more we disinvest, the more harm we see come to those communities and people who can least afford the ability to cope with said harms. The further we lower the bar on medically focused sex education, the more likely young people will have to face higher rates of youth pregnancy, HIV, and STIs. The more we see attacks on and defunding of health departments, the fewer people are going to want to work there.

We need the political will, the private support, and collaborative spirit of advocates across issue areas to face this moment. Syphilis untreated or untreatable is deadly, gonorrhea and chlamydia untreated or untreatable can and will render people infertile among other permanent injuries to internal organs, and untreated HIV and HCV is also deadly. The communities most affected by these illnesses are also least likely to be able to afford health care, housing, and have adequate health insurance. The people most affected by these illnesses are often Black, Brown, young, queer, or assigned female at birth. We need to care more about achieving health Justice and we need to do it together.

Biden’s State of the Union: Bold Promises on Public Health

On March 1st, President Biden delivered his first State of the Union Address to both chambers of Congress and the American people at large. Amid a slew of foreign and domestic policy proclamations, particular attention should be afforded to the statements and commitments made about addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and public health, more broadly. Championing the landmark legislation that was the American Rescue Plan, the President laid out how the legislation’s programming reduced food pantry lines, increased employment, and how expansion of the Affordable Care Act’s subsidies resulted in lower insurance premiums for many Americans. In addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, Biden also recognized a sobering outcome that will shake the nation: within the next few weeks, the United States’ official COVID death toll will surpass one million people. Though the President misstated the moment in that those empty seats at dinner tables will be more than a million; on average each COVID death has impacted 9 other people, including orphaning children across the country. Biden then shifted the address, citing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recent announcement of adjust masking guidelines and metrics of risk, trying to signal a much-needed political win in the fight against COVID. However, immediately following these statements, the President also focused on providing the country with another round of free at-home COVID-19 tests and implementing a tactic already well-known in the HIV space: test-to-treat, with added bonus of the program following the COVID vaccine model and having no out-of-pocket expense for patients.

The program ideals outlined in the days that followed found some confusion, need for clarity, and even some professional association bickering. Public health professionals who have long advocated for more robust responses to the pandemic took to news outlets to vent their frustrations and the American Medical Association drew derision on social media for their statement discouraging pharmacists prescription and provision of COVID antivirals. Pharmacists have long been a target for HIV advocates, especially in terms of increasing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access and decreasing test to treat initiation delays. Wouldn’t it be nice if this COVID program provided a model outside of vaccination in which pharmacists could also serve a more robust role in facilitating seamless treatment and prevention? The meaningful hiccups the administration and advocates should keep a close eye on in this regard is the labor shortage of pharmacists, closing of more rural locations for chain pharmacies, and any developments around anti-competitive practices of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) associated with pharmacies. Consequences of these will extend beyond immediate COVID programming and ideal HIV programming.

The President also made statements referring to medication costs and price controls and needing to make sure more Americans could afford their care. However, details were lacking and if any recent effort is indicative, singularly focusing on manufacturer list prices won’t address patient costs or get much anywhere. Buyer beware, some proposals in the apparently sunk Build Back better legislation would also cut provider compensation in public payer programs, a dire consequence as the nation struggles with health care staffing shortages. Those shortages should be noted in detail because the American Rescue Plan provided funding meant to supplement the financial demands of staffing a pandemic and there’s good reason to suspect administrators, rather than providers, enjoyed the fruits of that labor. Further, most Americans experience their out-of-pocket costs of care due to the benefit design of their insurer (and PBM), not the manufacturer list price. Indeed, the Biden Administration appears to eb as insurer friendly as the Obama admin. To impact the costs facing patients more meaningfully at the pharmacy counter and other burdens in accessing medication, the Biden administration should focus more on developing patient protections via the regulatory process, limiting the aggressive utilization management (or deny-first coverage) policies, increasing formulary restrictions, and discriminatory plan design. Some of the tools for doing so already exist, but the federal government has yet to curb the tactics of payers in avoiding their responsibilities under the ACA’s medical-loss-ratio rules or ensure payers are not inappropriately applying cost-sharing for qualifying preventative medications and services.

The President also became the first to mention “harm reduction” in a State of the Union Address. Urging Congress to pass the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act (MAT Act), President Biden is seeking to fulfill his commitments to address the opioid epidemic and move toward modernizing domestic drug policy. In a sign of acknowledgment of the scope and size of substance use epidemic in the country, Biden endorsed recovery programs and recognized the more than 23 million people struggling with addiction in the country. Immediately following the MAT Act mention, the President moved on to address of a lesser defined but equally important need in encouraging commitment to a robust set of policy ideals aimed at meeting the mental health needs of the country.

All these good things can easily be outweighed by what wasn’t mentioned. President Biden did not mention any interest in extending another round of stimulus payments, despite the program resulting in one of the largest reductions in poverty in US history. And while there was focus on rebuilding the nation’s health care staffing, no mention was afforded to rebuilding the nation’s public health infrastructure. Meanwhile, we’ve known for quite some time poverty as a notable association with HIV and decreasing poverty also decreases HIV risks and prevalence, data remains in the decline with regard to HIV and STI screenings, Hepatitis C rates are still on the rise, and inconsistencies in PrEP usage during the height of initial COVID waves likely foretells a more diverse at-risk community. Even the government’s own HIV.gov webpage dedicated to the State of the Union fails to mention any HIV or HCV specific programming efforts associated with the address.

While there’s much to celebrate about the President’s COVID goals, advocates should be cautious about projecting those goals onto other public health efforts. Afterall, COVID proved we could provide more up to date reporting than the 2 year delays we typically see in HIV and HCV surveillance, but we haven’t. COVID-related telemedicine expansion was welcomed by patients across the nation but Congress is poised to claw back those gains. For many of us, while the state of the union is improving coming out of the Omicron wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, much work remains. Including reminding this administration that it is empowered to protect patients, access to and affordability of care, an obligation to invest in public health programs beyond COVID and has committed to advancing efforts to End the HIV Epidemic.

HIV & Covid-19: A Story of Concurrent Pandemics

On September 20th, Johns Hopkins’ COVID data tracker totaled the “confirmed” (note: not “official”) number of deaths from COVID-19 in the United States to surpass 675,000 – or the estimated number of deaths in the US due to the 1918-1919 H1N1 influenza pandemic (colloquially called the “Spanish flu” because Spanish media were more willing to discuss the pandemic than most other countries). Forbes, STAT, and other large news outlets ran headlines like “Covid-19 overtakes 1918 Spanish flu as deadliest disease in American history” or included statements in their articles like “It was the most deadly pandemic in U.S. history until Monday, when confirmed coronavirus deaths overtook the death toll for the Spanish Flu.”

Which, as Peter Staley pointed out, isn’t factually accurate.

Image: Twitter.com - @peterstaley (Sep 20, 2021) “Um, HIV/AIDS? 700,000 U.S. deaths (and counting), according to the http://HIV.gov https://hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview”

Staley would quickly admit COVID-19 would or already has likely overcome the death toll of HIV in the United States. While I agree with this analysis, I would add “for now”.

The very nature of HIV has made finding a “cure” or vaccine for the virus an oft sought after “holy grail” in pharmaceutical development. While that grail may have been snatched away by the attention COVID-19 is justly generating, this isn’t the first concurrent pandemic HIV has run alongside. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) both refer to the H1N1 influenza outbreak of the 2009-2010 flue season a “pandemic”. The problem of course isn’t just how deadly COVID-19 is, its’ how botched the domestic and global responses have been to the disease.

Viruses, after all, are opportunistic. They have a singular purpose: reproduce. As such, viruses thrive in environments – ecosystems, if you will – that are sorely neglected, lack coordinated responses, and are largely inequitable. But we knew that. We’ve known that with regard to global and domestic health disparities data for decades. As with personal health, emerging, urgent issues in public health reduce our capacity to address existing issues effectively.

As I mentioned in previous blogs, and has been recently noted by the Global Fund, COVID-19 has drastically reduced the efficacy of existing HIV, HCV, STI, and SUD programs. Even still, Global Fund’s report proves a rather interesting point – when meeting the demands of advocates for programs to provide patients with multi-month supplies of medications, meeting people in their own neighborhoods rather than in clinics, and providing at-home testing kits, communities can be activated in care at an exceptional level. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic raging, the needs of the HIV pandemic didn’t stop. And while meeting those needs faltered some (with 4.5% fewer mothers receiving vertical transmission prevention medications, an 11% drop in prevention programming, and a 22% reduction in testing services), in some areas meeting those needs thrived. Global Fund’s report found South Africa was able to increase the number of people receiving antiretroviral therapies by more than three times the baseline, even while fighting on two fronts.

Dr. Sioban Crowley, Head of HIV at the Global Fund, pointed out these program designs are not exclusive to HIV, “If we can keep 21.9 million people on treatment, we can probably deliver them a COVID test and a vaccine.”

Indeed, with the United States’ (and the world’s) response relying heavily on expertise gained in the fight against HIV, one can reasonably ask “If we know how to beat this, why aren’t we…just doing that?”

“That” being what advocates have long asked for: a more dedicated, equitable landscape and adequate support of our public health systems. As with COVID-19, a vaccine won’t “cure” us of HIV if the rest of the world cannot access it. As with HIV, if preventative services, adequate testing, and necessary education are not readily made available to people where they are, we will continue to fail in both fights. If we don’t wish to repeat the losses we’ve already experienced in the fight against HIV, then we cannot keep making the same mistakes of kicking the costs of these investments down the road and maybe, eventually “getting to it”.

As has been said many times through the latest pandemic, “the best time to do the right thing was yesterday. The next best time to do the right thing is today.” It’s time for us to do the right thing and stop allowing backbone public health programs to fall by the wayside in the face of the next emergency. Today, for the next few years, it’s COVID. We don’t need to “wait” for that to end. There’s two pandemics occurring, it’s time we act like it.

Biden Administration’s Healthcare Future is One of Promise & Peril

Last month, the Biden Administration issued a press release outlining a look toward the future of American health care policy. Priorities in the presser include ever elusive efforts around prescription drug pricing and items with steep price tags like expanding Medicare coverage to include dental, hearing, and vision benefits, a federal Medicaid look-alike program to fill the coverage gaps in non-expansion states, and extending Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies enhancements instituted under the American Rescue Plan (ARP) in March. Many of these efforts are tied to the upcoming $3.5 trillion reconciliation package.

President Biden renewed his call in support of the Democrats effort to negotiate Medicare prescription drug costs, enshrined in H.R. 3. Drug pricing reform has been an exceptional challenge despite relatively popular support among the voting public, in particular among seniors. The pharmseutical industry has long touted drug prices set by manufacturers do not represent the largest barriers to care and mandating lower drug costs would harm innovation and development of new products. Indeed, for most Americans, some form of insurance payer, public or private, is the arbiter of end-user costs by way of cost-sharing (co-pays and co-insurance payments). To even get to that point, consumers need to be able to afford monthly premiums which can range from no-cost to the enrollee to hundreds of dollars for those without access to Medicaid or federal subsidies. The argument from the drug-making industry giants is for Congress to focus efforts that more directly impact consumers’ own costs, not health care industry’s costs. Pharmaceutical manufacturers further argue mandated price negotiation proposals would harm the industry’s ability to invest the development of new products. To this end, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released a report giving some credence to this claim. The CBO’s report found immediate drug development would hardly be impacted as those medications currently “in the pipeline” would largely be safe, but a near 10% reduction in new drugs over the next 30 years. While new drug development has largely been focused on “personalized” medicine – or more specific treatments for things like cancer – implementing mRNA technology into vaccines is indeed a matter of innovation (having moved from theoretical to shots-in-arms less than a year ago). With a pandemic still bearing down on the globe, linking the need between development and combating future public health threats should be anticipated.

The administration’s effort to leverage Medicare isn’t limited to drug pricing. Another tectonic plate-sized move would seek to expand “basic” Medicare to include dental, hearing, and vision coverage. Congressional Democrats, while generally open to the idea, are already struggling with timing of such an expansion, angering Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) by suggesting a delay until 2028. While any patient with any ailments related to their oral health, hearing, and vision will readily tell you these are critical and necessary coverages, even some of the most common of needs, the private health care insurance industry generally requires adult consumers to get these benefits as add-ons and the annual benefit cap is dangerously low (with dental coverage rarely offering more than $500 in benefit and vision coverage capping at one set of frames, both with networks so narrow as to be near meaningless for patients with transportation challenges). While the ACA expanded a mandatory coverage for children to include dental and vision benefits in-line with private adult coverage caps, the legislation did nothing to mandate similar coverages for adults and did not require private payers to make access to these types of care more meaningful (expanded networks and larger program benefits to more accurately match costs of respective care).

The other two massive proposals the Biden Administration is seeking support for, more directly impact American health care consumers than any other effort from the administration: maintaining expanded marketplace subsidies and a federal look-a-like for people living in the 12 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion provisions. The administration has decent data to back this idea, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report showing a drop in the uninsured rate from 2019 to 2020 by 1.9 million people, largely attributed by pandemic-oriented programs requiring states to maintain their Medicaid rolls. The administration and Congressional Democrats are expected to argue subsequently passed legislation allowing for expanded subsidies and maintained Medicaid rolls improved access to and affordability of care for vulnerable Americans during the pandemic. As the nation rides through another surge of illness, hospitalizations, and death from the same pandemic “now isn’t the time to stop”, or some argument along those lines, will likely be the rhetoric driving these initiatives.

Speaking of the pandemic, President Biden outlined his administration’s next steps in combating COVID-19 on Thursday, September 9th. The six-pronged approach, entitled “Path out of the Pandemic”, includes leveraging funding to support mitigation measures in schools (including back-filling salaries for those affected by anti-mask mandates and improving urging the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] to authorize vaccines for children under the age of 12), directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to issue a rule mandating vaccines or routinized testing for employers with more than 100 employees (affecting about 80 million employees) and mandating federally funded health care provider entities to require vaccination of all staff, pushing for booster shots despite the World Health Organization’s call for a moratorium until greater global equity in access can be attained, supporting small businesses through previously used loan schemes, and an effort to expand qualified health care personnel to distribute COVID-19 related care amid a surge threatening the nation’s hospitals ability to provide even basic care. Notably missing from this proposal are infrastructure supports for schools to improve ventilation, individual financial support (extension of pandemic unemployment programs or another round of direct stimulus payments), longer-term disability systems to support “long-COVID” patients and any yet-unknown post-viral syndromes, and housing support – which is desperately needed as the administration’s eviction moratorium has fallen victim to ideological legal fights, states having been slow to distribute rental assistance funds, and landlords are reportedly refusing rental assistance dollars in favor of eviction. While the plan outlines specific “economic recovery”, a great deal is left to be desired to ensure families and individuals succeed in the ongoing pandemic. Focusing on business success has thus far proven a limited benefit to families and more needs to be done to directly benefit patients and families navigating an uncertain future.

President Biden did not address global vaccine equity in his speech, later saying a plan would come “later”. The problem, of course, is in a viral pandemic, variant development has furthered risks to wealthy countries with robust vaccine access and threatened the economic future of the globe.

To top off all of this policy-making news, Judge Reed O’Connor is taking another swing at dismantling some of the most popular provisions of the ACA. Well, rather, yet another plaintiff has come to the sympathetic judge’s court in an effort to gut the legislation’s preventative care provisions by both “morality” and “process” arguments in Kelley v. Becerra. The suit takes exception to a requirement that insurers must cover particular preventative care as prescribed by three entities within the government (the Health Resources Services Administration – HRSA, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices – ACIP, and the Preventative Services Takes Force – PSTF), which require coverage of contraceptives and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with no-cost sharing to the patient, among a myriad of other things – including certain vaccine coverage. By now, between O’Connor’s rabid disregard for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans and obsessive effort to dismantle the ACA at every chance he can – both to his own humiliation after the Supreme Court finally go their hands on his rulings – Reed O’Connor may finally have his moment to claim a victory – I mean – the plaintiffs in Kelley may well succeed due to the Supreme Court’s most recent makeover.

As elected officials are gearing up for their midterm campaigns, how these next few months play out will be pretty critical in setting the frame for public policy “successes” and “failures”. Journalists would do well to tap into the expertise of patient advocates in contextualizing the real-world application of these policies, both during and after budget-making lights the path to our future – for better or worse.

Amid HIV Outbreaks, Covid-19 Fractures Existing Public Health Efforts

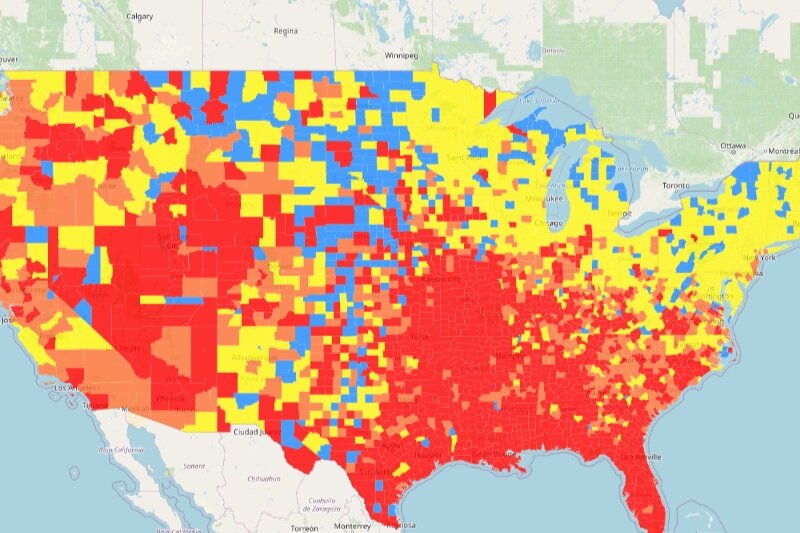

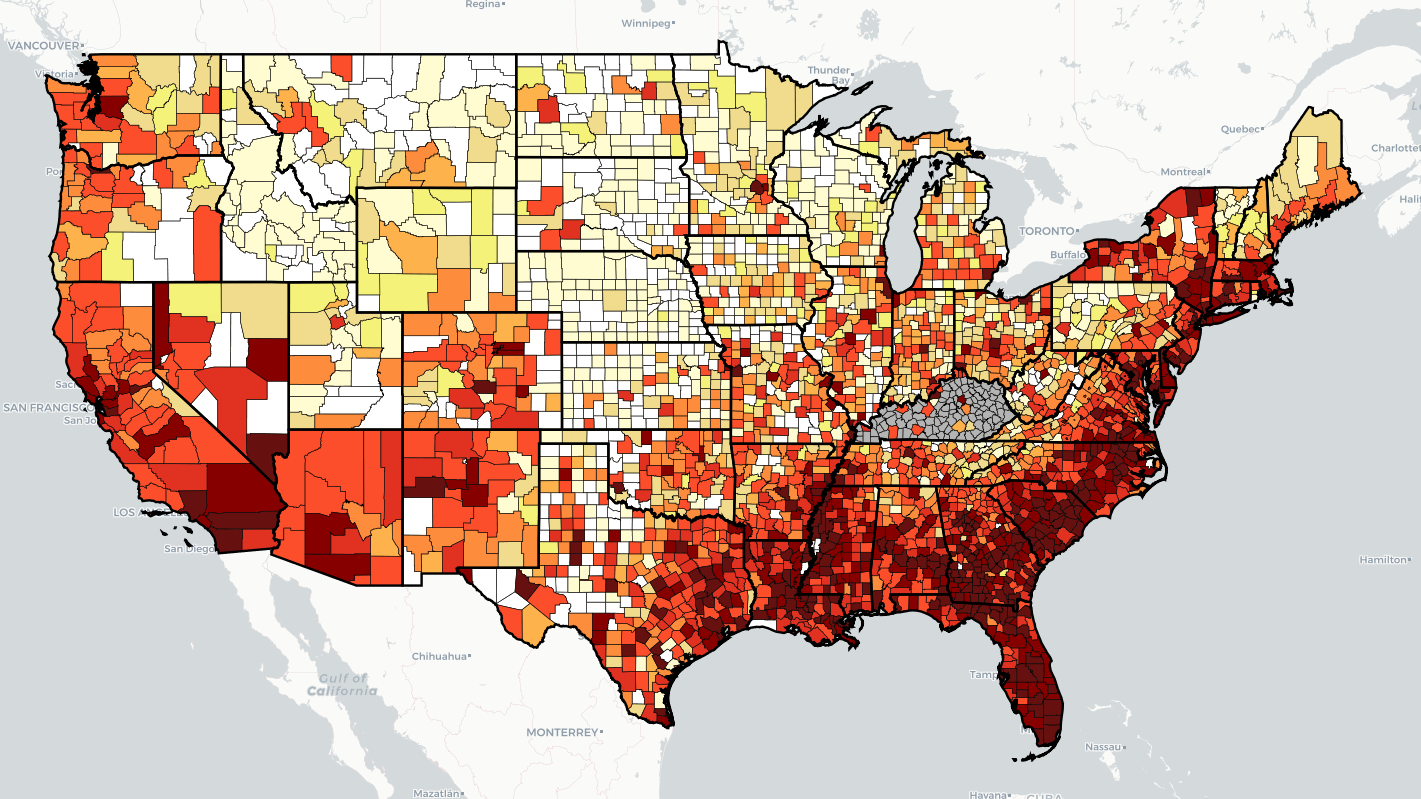

“Every health disparity map in the United States is the same,” Alex Vance, Senior Director of Advocacy and Public Policy at the International Association of Providers in AIDS Care, has repeatedly stated when discussing the COVID-19 pandemic and the very real risks of “back sliding” in our moderate advancements in the United States’ effort to End the HIV Epidemic. There’s no better way to demonstrate this than by showing you.

As another “wave” of Covid-19 ravages the country, increasing cases, hospitalization rates, and eventually deaths, existing public health needs around HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections continue to be strained, pushed to the back burner and most often in geographic areas where we need to be able to juggle more, not less; particularly across the South. Unlike Covid-19 outbreaks, which receive fairly immediate attention in terms of reporting and response, HIV outbreaks can and do often take a year or more to notice and begin action to address. While there’s concern about juggling the demands of addressing concurrent pandemics, some (certainly not all) of this reporting and response is beginning to speed up with regard to HIV.

West Virginia’s Kanawha County HIV outbreak is considered a 2020 outbreak, though just recently received a report from the Center’s for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) on next steps and recommendations to address. Despite these recommendations including supporting syringe exchange programs and community-based services, local officials continue a politically oriented response by seeking to limit the support of syringe exchange programs, threatening their ability to operate and aid in addressing the needs of the local community. Another outbreak in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula was identified in July of this year, with rural Kalkaska County reporting a higher rate of new HIV diagnoses than even Detroit. Kalkaska County is so similarly situated to Scott County, Indiana, it’s striking. Louisville, Kentucky has reported almost as many new HIV diagnoses in the first half of 2021 as the area does annually. And Duluth, outside of Saint Louis, Minnesota, joined neighboring Hennepin and Ramsey Counties with declared outbreaks tied to 2019 and 2018, respectively.

What’s important to note about 2020’s marked reduction in HIV screenings is not just the delay in newly diagnosing people living with HIV, but the lack of ability to link people to care upon diagnosis, beginning antiretroviral therapy and taking steps to reduce the person’s viral load. With at-home testing being the substitute offering, linkage to care and counseling for people self-testing may be hampered according to some concerned advocates. Achieving viral suppression also reduces the possibility of transmitting HIV by way of sexual contact to zero (“Undetectable = Untransmittable”) – creating a process where people living with HIV are not just a patient group needing identification, but play a critical role in preventing new transmissions.

In reviewing the possibilities of delayed care and delayed screening, public health officials and advocates should remember a new diagnosis is not necessarily indicative of a new transmission. A potential problem in and of itself, in assessing Covid-19 disruptions in screening and care, is the possibility of a “bottle neck” of new testing revealing new HIV diagnoses which otherwise might have been identified in the previous year if not for stay-at-home orders, education and public awareness campaigns, and community health care providers having had to take a step or shift gears entirely from HIV to Covid-19. It will take years for us to truly understand the breadth and reach of Covid-19 on the world’s only concurrent pandemic, even in the “most advanced country in the world”.

What can already be well-appreciated and should be well-understood is we cannot afford to keep asking community-based health care providers and community partners in combatting the domestic HIV epidemic to keep sacrificing HIV screening and linkage to care in order to address Covid-19. What must be prioritized is funding, programming, training, and most importantly hiring of new talent in addition to existing programs in order to address both sets of needs.