Prescription Drug Advisory Boards: Who is Impacted and How to get Involved

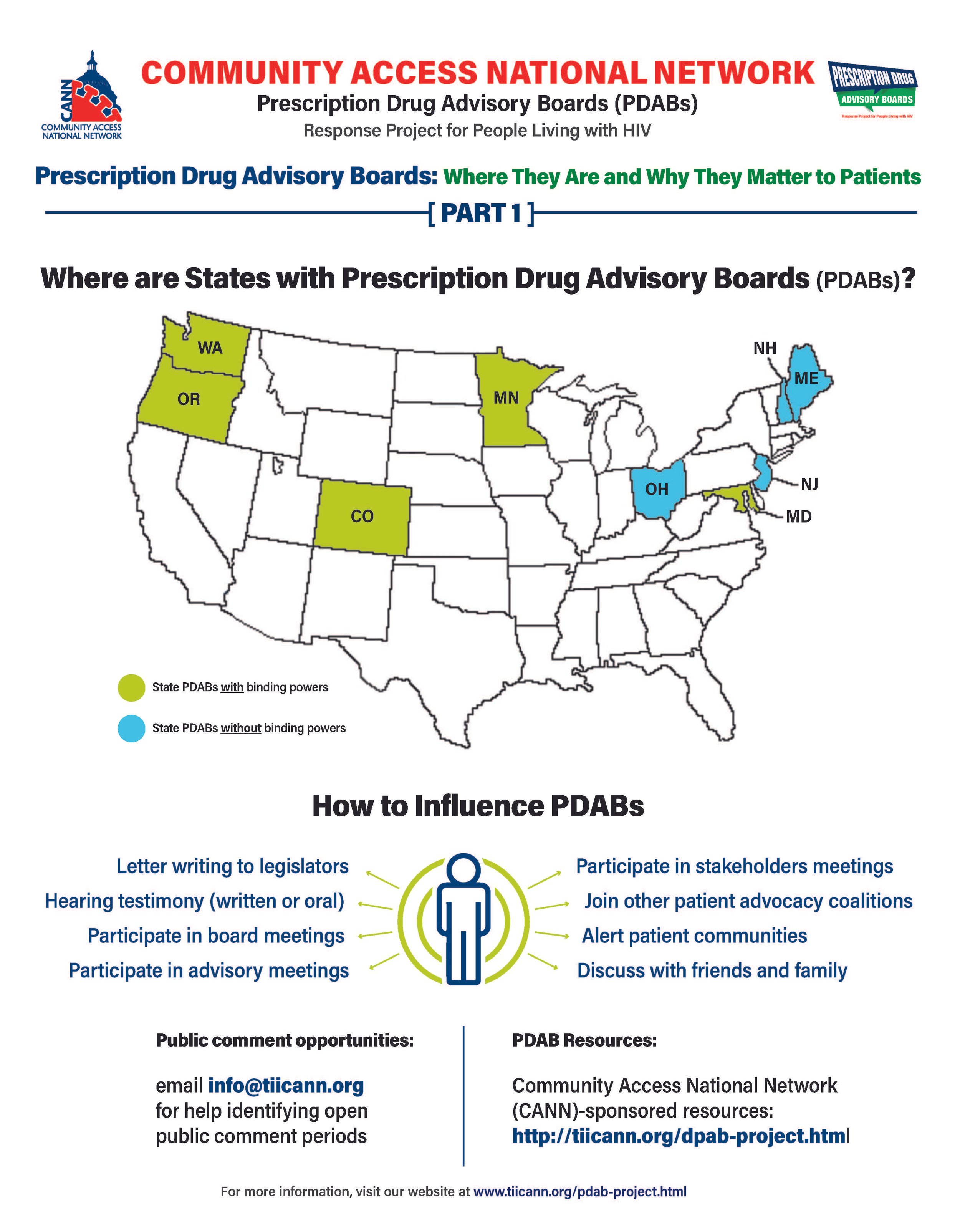

The prescription drug advisory board (PDAB) train keeps chugging along. Presently, there are nine (9) states that had, have or are in the process of enacting PDAB legislation: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maryland, and Maine. Ohio, it would seem, has abandoned their PDAB efforts. Their geographical variance reflects the diversity of their structures. Some of the boards have five members, and some have seven. While all are appointed by the governor, they differ regarding which departments they are associated with. For example, Colorado’s is associated with the Division of Insurance, and Oregon’s is associated with the Department of Consumer and Business Services.

The assortment of structure does not stop at department association. The number of drugs to be selected annually for review also varies, such as Colorado with five and Oregon with nine. Even the number of advisory council members lacks consistency. The New Jersey DPAB advisory council has twenty-seven (27) members, while Colorado’s has fifteen (15). Inconsistency in structure means inconsistency in operations. Thus, the help or harm patients ultimately receive will vary drastically from state to state. The most important differences are the powers bestowed upon the various DPABs. In addition to shaping many policy recommendations, five (5) currently have the ability to enact binding upper payment limit (UPL) settings: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Maryland, and Minnesota.

An upper payment limit sets a maximum for all purchases and payments for expensive drugs. By setting UPLs for high-cost medications, improved ability to finance treatment equals greater access to high-cost medicines. A UPL sets a ceiling on what a payor may reimburse for a drug, including public health plans, like Medicaid.

Patients, advocates, caregivers, and providers are concerned about PDABs because the outcomes of theory versus practice can have dire consequences. Theoretically, PDABs should reduce what patients spend out of pocket for medications and lower government prescription drug expenditures. However, the varied ways different PDABs are set to operate could jeopardize goals. Focusing on lowering reimbursement rates could affect the funds used as a lifeline by organizations benefiting from the 340B pricing program even while not meaningfully reducing patient out-of-pocket costs. If reimbursement limits are set too low, those entities will have drastic reductions in the funding they use for services for the vulnerable populations they serve. UPLs could ultimately increase patients' financial burden if payers increase cost-sharing and change formulary tiers to offset profit loss from pricing changes or institute utilization management practices like step-therapy or prior authorization. Increasing patient administrative burden necessarily decreases access to medication. When patients are made to spend more time arguing for the medication they and their provider have determined to be the best suited for them, rather than simply being able to access the medication, the more likely patients are to have to miss work to fight for the medication they need or make multiple pharmacy trips – or suffer the health and financial consequences of having to “fail” a different medication first. PDAB changes could affect provider reimbursement, which could be lowered with pervasive pricing changes. Decreased provider reimbursement could result in additional costs being passed onto patients or, in the situation of 340B, safety-net providers, reduce available funding for support services patients have come to rely upon.

The divergent factors that different PDABs use for decision-making are of concern as well. It is not enough to just look at the list price of drugs and the number of people using them. For example, some worthwhile criteria for consideration of affordability challenges codified in Oregon’s PDAB legislation are: “Whether the prescription drug has led to health inequities in communities of color… The impact on patient access to the drug considering standard prescription drug benefit designs in health insurance plans offered…The relative financial impacts to health, medical or social services costs as can be quantified and compared to the costs of existing therapeutic alternatives…”. But few of these PDABs consider payer-related issues like limited in-network pharmacies, discriminatory reimbursement, patient steering mechanisms, or frequency of utilization management as hindrances to patients getting our medications.

Effectively seeking and considering input from patients, caregivers, and frontline healthcare providers is also of concern. The legislation of various DPABs specifies the conflicts of interest that board members cannot have and must disclose. Some even have appointed alternates to allow board members to recuse themselves from making decisions on drugs with which they have financial and ethical conflicts. However, most of the advisory boards are providers, government, and otherwise industry-related. The board members are even required to have advanced degrees and experience in health economics, administration, and more. The majority of the discourse is not weighted towards the patient and our advocates. Few, if any, specific active outreach measures when it comes to seeking patient input. For example, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program requires patient and community engagement outlets in planning activities. But no PDAB legislation, to our knowledge, requires PDABs to engage with these established patient-oriented consortia. We know well in HIV that expecting already burdened patients often struggle to meet limit engagement opportunities from government boards – we know the very best practices are going to patients, rather than expecting patients to come to these boards. Beyond these limited engagement opportunities and failure to reach out to spaces where patients are already engaged, some states have exceptionally short periods in which to gather these inputs.

However, depending on the individual state’s DPAB structure, there is an opportunity for patients, caregivers, and organizations to give input through public comment periods and particular meetings aimed at stakeholder engagement. For states considering PDAB legislation, like Michigan, patients can and should engage in the legislative process. One place to keep abreast of different state’s PDAB activities is the Community Access National Network’s PDAB microsite. The microsite has an interactive map where you can access various states’ PDAB sites as they are created. States with fully formed PDABs have sites that display their scheduled meetings, previous decisions made, agendas for future sessions, and, most notably, details of the process for the public to provide input. Most of the meetings are open to the public, with the public invited to provide oral public comment or to submit written comments. Attending meetings and speaking directly to the boards is a way to have board members and others hear directly from those who will be affected by their decisions. Written public comment is also essential, especially from community patient advocacy organizations. Some DPABS also provide access to virtual meetings where stakeholders can provide feedback and input.

Medicare has six protected drug classes: anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antineoplastics, antipsychotics, antiretrovirals, and immunosuppressants. This means that Medicare Part D formularies must include them but that protection exists because we know how important these medications are. Antiretrovirals and oncology medications are a part of that list because adversely affecting the mechanisms of access to those drug classes is life-threatening to those who need them. It is imperative that continued scrutiny be placed upon DPABs to ensure that their benefits are patient-focused, like reducing administrative burden and barriers to care, rather than a mask that ultimately benefits payers by increasing their profits.

Prescription Drug Advisory Boards: What They Are and Why They Matter to Patients

It’s no secret that the high cost of healthcare is a significant concern for most Americans. The total national health expenditure in 2021 increased by 2.7% from the previous year to 4.3 trillion dollars which was 18.3% of the gross domestic product. The federal government held the majority of the spending burden at 34%, with individual households a close second at 27%. A cornerstone component of medical treatment is the access to prescription drugs. In 2019 in the U.S., the government and private insurers spent twice as much on prescription drugs as in other comparatively wealthy countries. Despite catchy phrases that poll well, and “simple” solutions by politicians that promise to fix the problem—such as Prescription Drug Advisory Boards (also known as Drug Pricing Advisory Boards)—it is mindful to remember one thing: if it sounds good to be true, then it probably isn’t true.

CANN PDAB infographic: What are they and why do they matter? (https://tiicann.org/dpab-project.html)

While list prices of prescription drugs continue to increase, medication costs do not represent the largest share of healthcare costs or the largest growth in healthcare costs in the United States. The cost burden on patients is so untenable for many that some have to decide between paying for medications, food, or mortgages. However, due to a number of incentives and the role of loosely regulated pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), there is little direct relationship between drug list prices and patient cost burdens. This fact is only just now being appreciated by lawmakers but is not currently reflected in our healthcare funding schemes. As such, the discourse surrounding lowering cost is a consistently turbulent sea navigated by diverse public and private parties, with the language around drug pricing assuming efforts to curb costs relate to patient costs and access – but not explicitly saying so (and for good reason). Some proposals are government related, such as federal drug pricing proposals. Recent developments are state-level focused closer to home. One such development is the Prescription Drug Advisory Boards, or PDABs.

PDABs are part of state divisions of insurance. Drug pricing efforts, in the general sense, could be a good thing. PDABs are being marketed to the public as a better means to make drugs more affordable for patients. However, the details of the implementation of developing PDABs are wherein lies significant challenges. Overall, the boards focus specifically on the prices of the drugs. However, the focus on pricing is mainly related to what governments, insurance companies, hospitals, and pharmacies are paying for the medications. This purview and the monitored metrics associated with PDABs do not necessarily translate into the actual costs patients pay at the pharmacy counter.

Because these designs are singularly focused on the “cost” to payors, current proposals and initiatives benefit both public and private payors at the expense of the patient access and the provider-patient relationship. It is unacceptable for any planned PDAB activity to disrupt the patient-provider relationship. Community Access National Network (CANN) has consistently opposed any policy initiative that might increase administrative barriers and patient burdens. Two examples are step-therapy and prior authorization. Activities such as these are considered what is known as utilization management. Utilization management helps lower prescription drug spending for public and private payors but creates additional costs for patients financially and logistically, affecting their continuity of care, amounting to a cost burden shift, not a meaningful increase of access to affordable, high-quality care and treatment for patients.

Additionally, the narrow specific focus on the list prices of drugs overlooks essential issues. Lowering the list price for medications can, for example, harm organizations that depend on revenues from the 340B Drug Pricing Program. The 340B program allows safety net clinics and organizations to purchase prescription drugs from manufacturers at a discounted price while being reimbursed by insurance carriers at a non-discounted cost. The surplus enables these entities to provide many services that the low-income populations they serve depend on. This is especially vital to low-income people living with HIV that do not have the means to afford all of their healthcare needs.

It is imperative that PDABs receive input directly from patients and caregivers as well. PDABs are aggregating a large amount of data. However, more of that data needs to include considerations of the patient experience. For example, drug rebate reductions can impact care and support services, such as transportation assistance or mental health services at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). Moreover, there needs to be an examination of the actual pass-through savings to patients. Most importantly, PDABs need to explore how pricing decisions affect patient access. A lower drug list price is not beneficial to patients if it creates or increases administrative burdens or increases costs for patients in other ways outside of paying for the cost of medication.

Most policymakers do not always have robust experience in understanding the nuances of dealing with public health programs, clinics, and populations. This is especially true regarding the marginalized community of people living with or at risk for acquiring HIV, those affected by Hepatitis C, or people who use drugs. PDABS must be held accountable for acquiring anecdotal qualitative and quantitative data regarding patient experience, accessibility, and affordability while developing recommendations related to drug pricing. As it stands, of the states that have implemented a PDAB, none have statutorily mandated metrics monitoring patient experience and access.

Patients, caregivers, and advocates with direct experience and greater understanding of the policy landscape around healthcare access play a vital role in helping to shape legislation and informing proper implementation of programs to meet the goals those programs were “sold” on. If monitored metrics do not consider or reflect patient experiences, then the program is simply not about increasing access for patients.

PDABs, fortunately, do have numerous opportunities for patients, caregivers, advocates, and providers to become involved and to elevate patient priorities over that of other stakeholders. Getting involved and staying involved with a state’s PDAB work is critically necessary to ensure any final work or regulation is patient-focused.

CANN will be present and offering feedback at various PDAB meetings in affected states. The next meeting CANN will be attending is virtual for the state of Colorado, on July 13th at 10am Mountain time. You can register here and participate in ensuring any action taken reflects patient needs.