PDAB Chicanery: How Drug Affordability Boards Are Undermining Public Engagement

Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) across the country are playing a dangerous game with public engagement—one where they keep changing the rules and moving the goalposts. From inadequate notice periods to last-minute document releases, these boards are creating barriers that echo troubling federal trends, effectively sidelining the very people who have the most at stake: patients.

These state-level games mirror concerning federal developments, most notably the rescinding of the Richardson Waiver by U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. This action removed a 50-year precedent requiring public input on HHS rules—effectively telling patients and advocates their opinions aren't welcome at the policy table.

As these transparency rollbacks continue, people who rely on medications face increasing uncertainty about their access to life-sustaining treatments—while boards claim to represent their interests through processes that actively exclude them.

Maryland PDAB: How to Follow the Letter of the Law While Breaking Its Spirit

Maryland's Prescription Drug Affordability Board offers a master class in technical compliance that functionally blocks meaningful public participation. Their recent meeting preparation tactics exemplify how these boards can check procedural boxes while effectively sidelining patient voices.

On March 18, 2025, the Maryland PDAB posted a revised agenda for their upcoming March 24 meeting. This might seem unremarkable until you realize the public comment deadline was March 19—giving stakeholders exactly one day to review, analyze, and formulate responses to complex pharmaceutical policy documents. The revised agenda wasn't a minor update either. It contained material differences from the previous version, including a comprehensive cost review dossier for Farxiga, a medication critical for many people with diabetes and heart failure.

As CANN's letter to the board noted, "Posting the updated agenda with associated meeting materials the day before the deadline for comment is not a good faith effort in garnering public trust, nor does it display value in public input." The Maryland PDAB's approach creates a veneer of public engagement while practically guaranteeing that meaningful input will be minimal.

This pattern suggests the board views public comment as a procedural hurdle rather than a valuable source of insight. By technically fulfilling their obligation to post materials before the comment deadline (even if by mere hours), they've found a convenient loophole that undermines the very transparency standards that public notice requirements are designed to uphold.

The Maryland case isn't an anomaly. It's a symptom of a growing tendency to treat public engagement as an inconvenient formality rather than a crucial component of sound healthcare policy development.

The Federal Parallel: HHS and the Richardson Waiver

The state-level PDAB maneuvers don't exist in a vacuum. They mirror a troubling federal precedent set by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who recently rescinded the Richardson Waiver—a decision that effectively slams the door on patient advocacy at the federal level.

The Richardson Waiver has a 50-year history. Established in 1971, it required HHS to subject matters relating to "public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts" to the American Procedures Act's notice and comment rulemaking guidelines. This waiver was created specifically to ensure public voices would be heard on matters that directly affect their health and well-being.

Now, that protection is gone. The new HHS rule claims the waiver "impose[s] costs on the Department and the public, are contrary to the efficient operation of the Department, and impede the Department's flexibility to adapt quickly to legal and policy mandates." This bureaucratic language translates to a simple message: we don't care what you think.

God forbid they remember who they work for.

And the impact is far-reaching. While Medicare remains protected under separate provisions of the Medicare Act, critical programs like Medicaid, SAMHSA, and the Administration for Children and Families now operate without mandated public comment periods. Legal experts note this could allow for swift implementation of controversial measures like Medicaid work requirements without going through normal rulemaking processes.

The timing is particularly ironic given the Office of Management and Budget's recent guidance letter emphasizing the importance of "broadening public participation and community engagement" and making it "easier for the American people to share their knowledge, needs, ideas, and lived experiences to improve how government works for and with them."

This federal retreat from transparency sets a dangerous tone that state-level boards appear eager to follow.

Other State PDAB Examples: Oregon and Colorado's Concerning Patterns

Maryland isn't alone in its questionable approach to public engagement. Oregon's PDAB recently decided to include Odefsey—an antiretroviral medication for people living with HIV—on its list for cost control exploration, contradicting previous discussions to protect these medications. While they claim they might reconsider based on affordability research, this flip-flop creates unnecessary anxiety for people who depend on these treatments.

Colorado's PDAB situation is particularly egregious. Since 2023, CANN has repeatedly requested that the board consult with the state health department about rebate impacts on public health infrastructure and patient affordability—concerns echoed by the former SDAP director and PDAB members themselves.

Yet Colorado PDAB staff have consistently avoided conducting a proper fiscal impact analysis, bluntly stating "We won't be doing that" when asked directly. This refusal persisted even as formal rulemaking began, which triggers statutory requirements for analyses under Colorado's Administrative Procedure Act.

The board has repeatedly postponed its first rulemaking hearing, effectively delaying compliance with transparency requirements. Meanwhile, the Joint Budget Committee has begun questioning the PDAB's financial accountability, receiving only partial responses about consultant costs and litigation expenses.

Most concerning is the disconnect between PDAB actions and demonstrated patient benefits. A 2024 analysis of Oregon's similar program showed states would need additional funds to maintain programs under an upper payment limit system—with no meaningful patient affordability improvements identified.

Patient Impact: Why This Matters

Behind the procedural games and policy maneuvers are real people whose lives hang in the balance. The Colorado PDAB's actions exemplify how these bureaucratic decisions create genuine fear and uncertainty for people with rare diseases and conditions requiring specialized medications.

Twelve-year-old Avery Kluck lives with Aicardi syndrome and faces life-threatening seizures that have been intensifying. Her doctors recommended Sabril, a powerful anticonvulsant costing up to $10,000 per month—a medication on Colorado's PDAB radar for potential price controls.

"We're to a point now where her seizures are getting more violent, and this is our last resort," explains Heather Kluck, Avery's mother. "And now I'm finding out she may not have access to it." The family faces an impossible choice between starting a medication that might become unavailable or watching their daughter suffer.

This uncertainty isn't theoretical. At least one pharmaceutical company has already threatened to pull drugs from Colorado if price caps are imposed. For medications like Sabril, which are dangerous to discontinue abruptly, such market exits could be catastrophic.

People living with cystic fibrosis also had to mobilize to prevent Colorado's PDAB from declaring Trikafta "unaffordable," with one parent describing the experience as "torturous for our family" and another stating: "It's an experiment, and it's really gross that they're doing it on people who are really sick."

The irony is painful: boards created to increase medication access may end up restricting it for those who need it most.

Conclusion

These boards, created under the guise of helping patients afford medications, are operating in ways that actively silence patient voices. From Maryland's last-minute document dumps to Colorado's refusal to conduct impact analyses and Oregon's policy reversals on critical medications, these boards are erecting barriers that exclude the very people who will bear the consequences of their decisions.

The problems run deeper than procedural failures. The fundamental approach of PDABs—attempting to control drug prices without adequately assessing impacts on patient access—risks creating catastrophic unintended consequences for people who depend on specialized medications. Avery Kluck and others living with rare conditions don't have the luxury of waiting while boards experiment with price controls that might make their life-saving treatments unavailable.

The pattern is clear: from the federal level with RFK Jr.'s dismantling of public comment protections to state PDABs playing administrative games, we're witnessing a coordinated retreat from meaningful public engagement in healthcare policy. This isn't just bad governance—it's dangerous for patients.

States should seriously reconsider whether PDABs serve any legitimate purpose beyond political theater. At minimum, stakeholders across the healthcare spectrum must demand that these boards either implement truly transparent, patient-centered processes or acknowledge they cannot fulfill their stated mission without causing harm to the very people they claim to help.

Prescription Drug Affordability Boards and the ADA: A Potential Conflict?

Could state efforts to lower prescription drug prices inadvertently violate a federal civil rights law? It’s a question being asked about Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) as they gain traction across the United States. PDABs are state-level entities designed to address the soaring cost of prescription medications, a crisis impacting millions of Americans. As policymakers seek solutions to improve affordability, PDABs have emerged as a popular strategy, with a growing number of states enacting legislation to establish these boards. While the intent behind PDABs is laudable, their implementation requires careful consideration to ensure they do not inadvertently create barriers for people with disabilities. The potential conflict between well-intentioned affordability initiatives and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) highlights the need for vigilance to protect the rights of people with disabilities in the pursuit of lower drug prices. Our analysis reveals that PDABs are disproportionately focusing on medications used to treat conditions likely classified as disabilities under the ADA, raising concerns about potential ADA violations.

A Disproportionate Focus on Drugs for Disabilities

A recent analysis conducted by Community Access National Network (CANN) reveals a concerning trend: PDABs are disproportionately targeting medications used to treat conditions highly likely or likely to be classified as disabilities under the ADA. This finding raises serious questions about the potential for PDABs to create disparate impact and limit access to essential medications for people with disabilities.

The table below summarizes the key data points from the CANN Data Analysis Report:

| State | Total Drugs Eligible | HIGHLY LIKELY | LIKELY | Total Potentially Disabling | % Potentially Disabling | % HIGHLY LIKELY | % LIKELY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO-E | 343 | 306 | 28 | 334 | 97.4% | 89.2% | 8.2% |

| CO-S | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 100% | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| MD | 8 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 100% | 37.5% | 62.5% |

| OR | 39 | 24 | 15 | 39 | 100% | 61.5% | 38.5% |

| WA | 188 | 94 | 68 | 162 | 86.2% | 50.0% | 36.2% |

Note: Percentages are based on the total number of drugs on each state's "Eligible for Review" list (or "Selected for Review" in Maryland's case), which represents the medications the PDAB could choose for a full affordability review. The Colorado data is presented in two rows: “CO-E” represents the 343 drugs eligible for review, and “CO-S” represents the four drugs ultimately selected for review by the PDAB. It is important to note that a lack of data transparency from some states limited our ability to perform a complete analysis for all PDABs. To determine a drug's relevance to this analysis, we evaluated each condition a drug treats based on its likelihood of being classified as a disability under the ADA, using a four-tiered ranking system: HIGHLY LIKELY, LIKELY, UNLIKELY, and VERY UNLIKELY.

In Colorado, 97.4% of the drugs initially eligible for review by the PDAB treat conditions categorized as “HIGHLY LIKELY” or “LIKELY” disabilities under the ADA. In Maryland and Oregon, every drug eligible for review falls into these categories. Even in Washington, where the percentage is lower, 86.2% of the drugs on the "Eligible for Review" list treat potentially disabling conditions.

This data demonstrates a clear pattern: PDABs are predominantly focusing on medications used by people with disabilities. This trend is particularly concerning given the variability and uncertainty surrounding PDAB processes for setting upper payment limits (UPLs), as highlighted by a recent analysis in Health Affairs.

A closer look at the specific condition categories targeted by PDABs further underscores this concern. In Colorado, the most frequently targeted categories include cancer, genetic disorders, autoimmune disorders, and hematological disorders. Maryland's PDAB focuses on endocrine disorders, autoimmune disorders, and respiratory disorders. Oregon’s list includes autoimmune disorders, addictive disorders, cancer, and endocrine disorders. Washington’s PDAB targets a similarly broad range of conditions, including autoimmune disorders, cancer, neurological disorders, and endocrine disorders. These categories encompass numerous conditions with a high likelihood of being classified as disabilities under the ADA.

The potential for PDABs to negatively impact people with disabilities is not merely hypothetical. In Colorado, the PDAB has already conducted affordability reviews on Enbrel and Stelara, two drugs used to treat conditions highly likely to be considered disabilities under the ADA. The Board determined that both medications are unaffordable, potentially leading to the establishment of UPLs, which would set limits on how much payers can reimburse for these drugs. If UPLs are set on these medications, it could significantly limit access for people who rely on them to manage their conditions.

Navigating the Legal Landscape: The ADA and Health Care

The disproportionate targeting of medications used by people with disabilities raises serious concerns about the potential for PDABs to violate the Americans with Disabilities Act. This landmark civil rights law prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in all areas of public life, including healthcare.

A key concept in ADA law is disparate impact. This occurs when a policy or practice, even if seemingly neutral on its face, has a disproportionately negative impact on people with disabilities. As legal scholar Sara Rosenbaum explains, "Disparate impact claims arise when a plaintiff can demonstrate that a facially neutral policy disproportionately burdens or harms people with disabilities." In the context of PDABs, disparate impact could occur if, for example, the setting of UPLs on medications for disabling conditions leads to greater utilization management or formulary restrictions, effectively limiting access for people with disabilities while having a less pronounced impact on people without disabilities. The potential for supply chain disruptions and the lack of guaranteed cost savings for patients, as highlighted in the recent Health Affairs article, further underscore the risk of disparate impact.

The ADA also requires covered entities, including healthcare providers and insurers, to provide reasonable accommodations to people with disabilities. Reasonable accommodations are adjustments to policies, practices, or procedures that enable people with disabilities to participate fully and equally in programs and services. However, the ADA does recognize that some accommodations may pose an "undue burden" on covered entities, meaning they would require significant difficulty or expense. The ADA National Network provides relevant examples in the healthcare context, such as modified meeting formats, accessible materials (e.g., large print, Braille), and the provision of sign language interpreters. PDABs must proactively incorporate reasonable accommodations into their processes to ensure meaningful participation for people with disabilities. This includes providing accessible meeting locations and materials, offering alternative formats for public comments, and ensuring that people with disabilities have equal opportunities to engage in the PDAB’s decision-making process.

Any limitations on access to medications resulting from PDAB actions must be justified by legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons. Historically, a common defense used to shield discriminatory coverage designs from legal challenges has been the "fundamental alteration" defense. This defense argues that modifying a benefit plan to accommodate the needs of people with disabilities would fundamentally alter the nature of the plan and is therefore not required under the ADA. However, the Affordable Care Act (ACA)'s emphasis on comprehensive coverage and non-discrimination weakens this defense. As the Supreme Court recognized in Alexander v. Choate, the benefit provided through a healthcare program is not merely the individual services offered, but also the opportunity for meaningful access to those services. The ACA's statutory language in Section 1557 reinforces this principle, prohibiting discrimination in benefit design and requiring coverage of essential health benefits. This shift in healthcare law strengthens the legal basis for challenging discriminatory PDAB practices that limit access to medications for people with disabilities.

The QALY Conundrum: Undervaluing Life with a Disability

Compounding the risk of discrimination in PDAB practices is the potential for these boards to rely on a flawed metric known as the Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) when evaluating drug affordability. The QALY is a measure used to assess the value of medical interventions by considering both the quantity and quality of life gained. While seemingly objective, the QALY inherently devalues life with a disability.

The problem lies in how the QALY calculates "quality" of life. It relies on societal perceptions of health and functioning, often derived from surveys of the general public. As the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) explains in a recent report, "The QALY equation relies on a baseline of 'perfect health' that is calculated by society’s conception of health and functioning." This means that people with disabilities are automatically assigned a lower quality-of-life score, regardless of their own lived experiences.

The DREDF report provides compelling examples of how the QALY can lead to discriminatory coverage decisions. For instance, the drug Trikafta, a breakthrough treatment for cystic fibrosis, has been shown to significantly extend the lives of people with this condition. However, because cystic fibrosis often involves functional limitations, the QALY undervalues the life extension benefit of Trikafta, potentially leading payers to deem it too expensive to cover. Similarly, medications for opioid use disorder, which can dramatically improve daily functioning and quality of life for people with this condition, are often undervalued by the QALY due to societal stigma and negative perceptions of opioid use disorder.

Some proponents of the QALY have proposed an alternative measure called the Equal Value of Life Years Gained (evLYG). The evLYG avoids discounting life extension based on quality of life. However, as the DREDF report points out, the evLYG fails to account for quality-of-life improvements, making it an incomplete solution.

The potential for PDABs to rely on QALY-based analyses is a serious concern. While some states explicitly prohibit the use of QALYs in setting UPLs, the lack of consistent language across all states and the continued focus on cost-related factors raise concerns about the perpetuation of bias in drug valuation. If PDABs utilize the QALY or similar metrics that fail to account for the true value of medications for people with disabilities, they risk exacerbating existing disparities and undermining the ADA’s guarantee of equal access to healthcare.

Can PDABs Overcome Inherent Bias in Drug Selection?

The establishment of PDABs, despite their purported goal of lowering drug costs, raises serious concerns about potential discrimination against people with disabilities. Our data analysis reveals a deeply troubling pattern: across all states examined, the vast majority of drugs targeted by PDABs are those used to treat conditions highly likely or likely to be classified as disabilities under the ADA. This striking trend, with some states demonstrating an exclusive focus on medications for potentially disabling conditions, calls into question the fundamental fairness and equity of PDAB drug selection processes.

This overwhelming focus on medications for potentially disabling conditions raises a fundamental question: can PDABs, as currently designed, ever truly operate in a manner that is equitable and non-discriminatory? The very nature of these boards, tasked with identifying "unaffordable" drugs and setting limits on their reimbursement, appears inherently biased against medications vital to the health and well-being of people with disabilities. Furthermore, the potential for PDABs to negatively impact the 340B Drug Pricing Program adds another layer of concern. As previous CANN articles have highlighted, UPLs set by PDABs could significantly reduce the revenue generated by 340B discounts, undermining a major source of funding for safety-net providers and jeopardizing access to care for vulnerable communities.

Proposals for mandatory ADA compliance reviews, data transparency, and stakeholder engagement, while necessary, are unlikely to fully address this fundamental flaw. Compliance reviews are reactive and cannot prevent all discriminatory outcomes. Data transparency, while necessary for accountability, does not guarantee equitable decision-making. And even meaningful engagement with disability rights organizations and people with disabilities cannot fully compensate for the inherent biases that may be embedded in PDAB processes.

Given the clear evidence of implicit bias in PDAB drug selection, more investment needs to be made in studying the potential discriminatory nature of these boards.

Quantify the Disparate Impact: Conduct comprehensive analyses to determine the extent to which PDAB drug selection and UPL-setting processes disproportionately impact people with disabilities.

Evaluate Alternative Strategies: Explore and compare the potential impact of various drug affordability strategies, including PDABs and alternatives such as direct price negotiations, expanded patient assistance programs, and bulk purchasing agreements, on access to medications for people with disabilities.

Develop Robust Safeguards: If states choose to move forward with PDABs, they must develop and implement comprehensive safeguards to mitigate the risk of discrimination. These safeguards should include mandatory ADA compliance reviews, comprehensive data transparency requirements, and meaningful engagement with disability rights organizations and people with disabilities throughout all stages of the PDAB process.

Addressing the complex intersection of drug affordability and disability rights requires a nuanced and evidence-based approach. Until we have a deeper understanding of the potential for discrimination and the efficacy of safeguards, the viability of PDABs remains in question.

Upper-Payment Limits; Drug "Affordability" Boards Risk Medication Access

The opinion piece, authored by Jen Laws, CANN’s President & CEO, originally published in the September 2, 2023, print edition of the Denver Post. CANN will be hosting a free “PDAB 101” webinar for patients, advocates, and all public health stakeholders on November 1, 2023. Pre-registration is required. Register by clicking here.

To successfully combat the HIV epidemic and defeat other chronic conditions, patients must have uninterrupted access to the most effective medicines recommended by their doctors. As efforts to ensure patients can access their medicines are being defined in the public sphere, many state legislatures continue to advance policies and proposals focused on addressing patient affordability challenges.

However, many such actions fail to address high out-of-pocket costs and instead focus on lowering costs for other stakeholders within the health care system, like lowering costs and increasing profits for health insurers neglecting the patients they were intended to protect.

In Colorado and several other states across the country, lawmakers have empowered Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) to address the rising costs that patients pay for prescription medicines. PDABs have the authority to select and review drug list prices and can recommend policies for drugs deemed "unaffordable." These list prices aren't something patients generally pay, rather we pay co-pays or are able to manage costs with patient assistance programs.

Despite this, one such policy being considered by the Colorado PDAB and similar boards in other states is an upper-payment limit (UPL). A UPL is a payment limit or ceiling that applies to all purchases and payments for certain high-cost drugs and does not necessarily translate into a "cost limit" for patients.

When UPLs are set, reimbursement rates are lowered for hospitals or clinics giving them less incentive to purchase specific drugs even though it may be the most effective medication to help a patient manage a chronic condition. When reimbursement rates are lowered through a UPL, it can also lead to barriers to biopharmaceutical companies investing in and supplying new innovative medicines to health facilities, making it difficult for doctors to prescribe treatments they think are best suited for their patients. While well intentioned, patients often bear the brunt of the challenges with such policies.

The impacts of the UPL process are only compounded when we consider the potential impact on the 340B Drug Pricing Program, a federal safety-net program that helps health facilities serve low-income and uninsured patients by offering them discounted drugs. Under the program, qualified clinics and other covered entities buy treatments at a discount to help treat vulnerable patients and get to keep the difference between the reimbursement rate and the discounted price leveraging those dollars to provide needy patients with medications and care they might not otherwise be able to afford.

Under a UPL, health facilities such as hospitals or clinics will receive lower reimbursements for prescribed treatments and therefore generate fewer dollars to support patients and the care we need to live and thrive. If the PDAB sets restrictive UPLs for drugs for chronic conditions like HIV, health facilities and the health professionals tasked with providing care will be faced with the decision to potentially stop prescribing these medicines and face having to cut support services that patients have come to rely on.

At a recent meeting of Colorado PDAB stakeholders, following the board's unanimous approval of the list of drugs eligible for an affordability review process, I voiced concerns about the approach to determining the value of lifesaving treatments for patients living with or at risk for HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and other complex conditions. My concerns have only grown since, most recently, the state PDAB selected five drugs to undergo a formal affordability review including a treatment for HIV.

Many patients and other stakeholders have raised alarm to other drugs that are now subject to review to treat complex conditions such as psoriasis, arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and cystic fibrosis. The implications of the Colorado drug "affordability" board's recent actions on patient access are grave and set a dangerous precedent. Ten states including Colorado have already established PDABs, and many others are following suit.

Those support services and continuity of care are critical to empower communities and improve the quality of life for people living with and managing conditions like HIV and hepatitis C. Despite the PDAB being "sold" to the public as a measure to improve patient experiences and access to care, the current model fails to prioritize patients at all.

Colorado is home to more than 13,000 people living with HIV and has been at the forefront of combating the disease. This year, state lawmakers advanced model legislation that protects patients' access to HIV prevention medication. However, the recent actions from the drug "affordability" board and short-sighted policies like the UPL process or mandatory generic switching could derail progress toward ending the HIV epidemic.

Price controls are, and will continue to be, a short-term, short-sighted "fix" with long-term consequences for patients living with chronic conditions. Policy efforts to address affordability must prioritize patient access and the ability for doctors to prescribe effective treatments. Colorado's PDAB, as it currently stands, falls short of that.

Prescription Drug Advisory Boards: Who is Impacted and How to get Involved

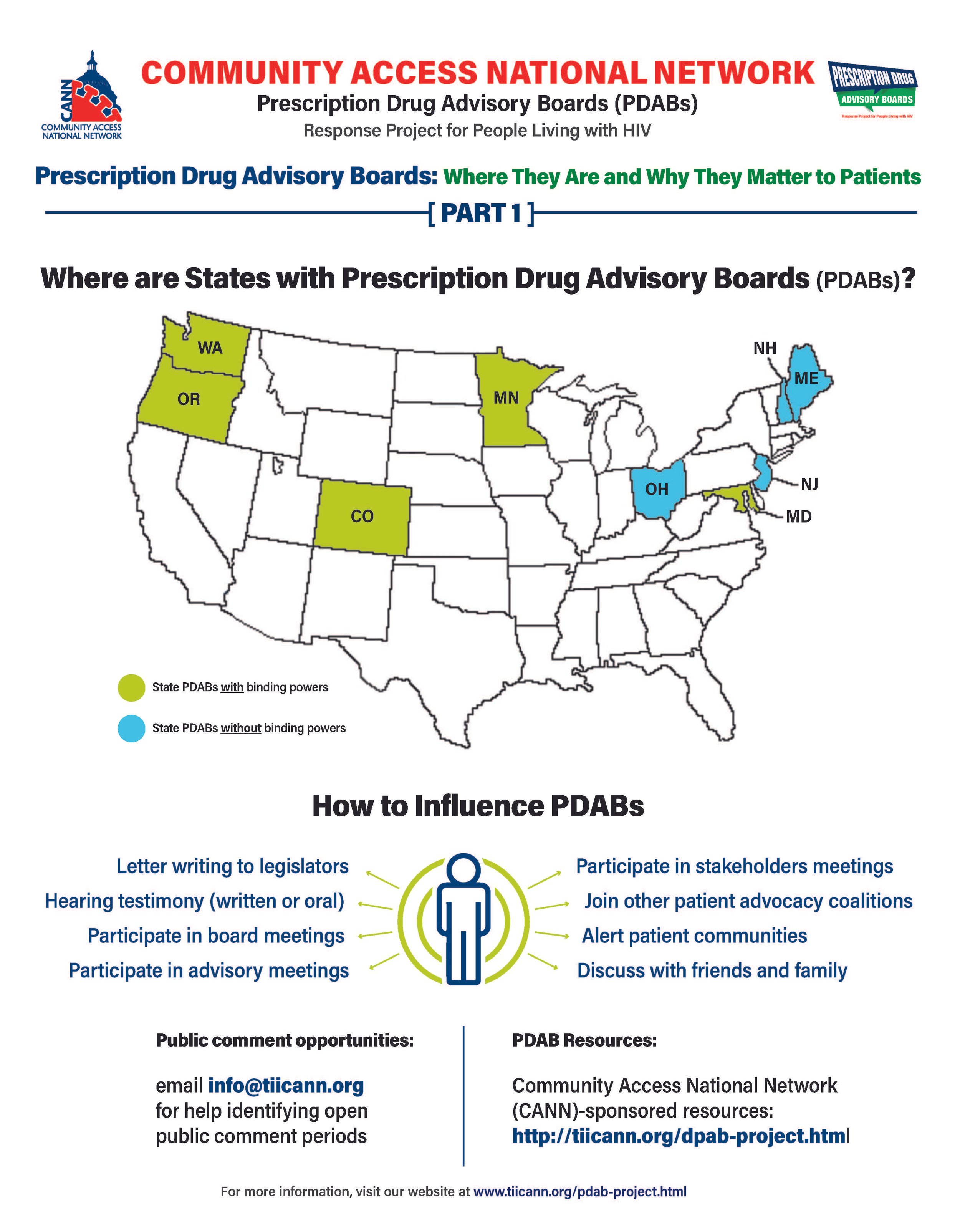

The prescription drug advisory board (PDAB) train keeps chugging along. Presently, there are nine (9) states that had, have or are in the process of enacting PDAB legislation: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maryland, and Maine. Ohio, it would seem, has abandoned their PDAB efforts. Their geographical variance reflects the diversity of their structures. Some of the boards have five members, and some have seven. While all are appointed by the governor, they differ regarding which departments they are associated with. For example, Colorado’s is associated with the Division of Insurance, and Oregon’s is associated with the Department of Consumer and Business Services.

The assortment of structure does not stop at department association. The number of drugs to be selected annually for review also varies, such as Colorado with five and Oregon with nine. Even the number of advisory council members lacks consistency. The New Jersey DPAB advisory council has twenty-seven (27) members, while Colorado’s has fifteen (15). Inconsistency in structure means inconsistency in operations. Thus, the help or harm patients ultimately receive will vary drastically from state to state. The most important differences are the powers bestowed upon the various DPABs. In addition to shaping many policy recommendations, five (5) currently have the ability to enact binding upper payment limit (UPL) settings: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Maryland, and Minnesota.

An upper payment limit sets a maximum for all purchases and payments for expensive drugs. By setting UPLs for high-cost medications, improved ability to finance treatment equals greater access to high-cost medicines. A UPL sets a ceiling on what a payor may reimburse for a drug, including public health plans, like Medicaid.

Patients, advocates, caregivers, and providers are concerned about PDABs because the outcomes of theory versus practice can have dire consequences. Theoretically, PDABs should reduce what patients spend out of pocket for medications and lower government prescription drug expenditures. However, the varied ways different PDABs are set to operate could jeopardize goals. Focusing on lowering reimbursement rates could affect the funds used as a lifeline by organizations benefiting from the 340B pricing program even while not meaningfully reducing patient out-of-pocket costs. If reimbursement limits are set too low, those entities will have drastic reductions in the funding they use for services for the vulnerable populations they serve. UPLs could ultimately increase patients' financial burden if payers increase cost-sharing and change formulary tiers to offset profit loss from pricing changes or institute utilization management practices like step-therapy or prior authorization. Increasing patient administrative burden necessarily decreases access to medication. When patients are made to spend more time arguing for the medication they and their provider have determined to be the best suited for them, rather than simply being able to access the medication, the more likely patients are to have to miss work to fight for the medication they need or make multiple pharmacy trips – or suffer the health and financial consequences of having to “fail” a different medication first. PDAB changes could affect provider reimbursement, which could be lowered with pervasive pricing changes. Decreased provider reimbursement could result in additional costs being passed onto patients or, in the situation of 340B, safety-net providers, reduce available funding for support services patients have come to rely upon.

The divergent factors that different PDABs use for decision-making are of concern as well. It is not enough to just look at the list price of drugs and the number of people using them. For example, some worthwhile criteria for consideration of affordability challenges codified in Oregon’s PDAB legislation are: “Whether the prescription drug has led to health inequities in communities of color… The impact on patient access to the drug considering standard prescription drug benefit designs in health insurance plans offered…The relative financial impacts to health, medical or social services costs as can be quantified and compared to the costs of existing therapeutic alternatives…”. But few of these PDABs consider payer-related issues like limited in-network pharmacies, discriminatory reimbursement, patient steering mechanisms, or frequency of utilization management as hindrances to patients getting our medications.

Effectively seeking and considering input from patients, caregivers, and frontline healthcare providers is also of concern. The legislation of various DPABs specifies the conflicts of interest that board members cannot have and must disclose. Some even have appointed alternates to allow board members to recuse themselves from making decisions on drugs with which they have financial and ethical conflicts. However, most of the advisory boards are providers, government, and otherwise industry-related. The board members are even required to have advanced degrees and experience in health economics, administration, and more. The majority of the discourse is not weighted towards the patient and our advocates. Few, if any, specific active outreach measures when it comes to seeking patient input. For example, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program requires patient and community engagement outlets in planning activities. But no PDAB legislation, to our knowledge, requires PDABs to engage with these established patient-oriented consortia. We know well in HIV that expecting already burdened patients often struggle to meet limit engagement opportunities from government boards – we know the very best practices are going to patients, rather than expecting patients to come to these boards. Beyond these limited engagement opportunities and failure to reach out to spaces where patients are already engaged, some states have exceptionally short periods in which to gather these inputs.

However, depending on the individual state’s DPAB structure, there is an opportunity for patients, caregivers, and organizations to give input through public comment periods and particular meetings aimed at stakeholder engagement. For states considering PDAB legislation, like Michigan, patients can and should engage in the legislative process. One place to keep abreast of different state’s PDAB activities is the Community Access National Network’s PDAB microsite. The microsite has an interactive map where you can access various states’ PDAB sites as they are created. States with fully formed PDABs have sites that display their scheduled meetings, previous decisions made, agendas for future sessions, and, most notably, details of the process for the public to provide input. Most of the meetings are open to the public, with the public invited to provide oral public comment or to submit written comments. Attending meetings and speaking directly to the boards is a way to have board members and others hear directly from those who will be affected by their decisions. Written public comment is also essential, especially from community patient advocacy organizations. Some DPABS also provide access to virtual meetings where stakeholders can provide feedback and input.

Medicare has six protected drug classes: anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antineoplastics, antipsychotics, antiretrovirals, and immunosuppressants. This means that Medicare Part D formularies must include them but that protection exists because we know how important these medications are. Antiretrovirals and oncology medications are a part of that list because adversely affecting the mechanisms of access to those drug classes is life-threatening to those who need them. It is imperative that continued scrutiny be placed upon DPABs to ensure that their benefits are patient-focused, like reducing administrative burden and barriers to care, rather than a mask that ultimately benefits payers by increasing their profits.

Prescription Drug Advisory Boards: What They Are and Why They Matter to Patients

It’s no secret that the high cost of healthcare is a significant concern for most Americans. The total national health expenditure in 2021 increased by 2.7% from the previous year to 4.3 trillion dollars which was 18.3% of the gross domestic product. The federal government held the majority of the spending burden at 34%, with individual households a close second at 27%. A cornerstone component of medical treatment is the access to prescription drugs. In 2019 in the U.S., the government and private insurers spent twice as much on prescription drugs as in other comparatively wealthy countries. Despite catchy phrases that poll well, and “simple” solutions by politicians that promise to fix the problem—such as Prescription Drug Advisory Boards (also known as Drug Pricing Advisory Boards)—it is mindful to remember one thing: if it sounds good to be true, then it probably isn’t true.

CANN PDAB infographic: What are they and why do they matter? (https://tiicann.org/dpab-project.html)

While list prices of prescription drugs continue to increase, medication costs do not represent the largest share of healthcare costs or the largest growth in healthcare costs in the United States. The cost burden on patients is so untenable for many that some have to decide between paying for medications, food, or mortgages. However, due to a number of incentives and the role of loosely regulated pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), there is little direct relationship between drug list prices and patient cost burdens. This fact is only just now being appreciated by lawmakers but is not currently reflected in our healthcare funding schemes. As such, the discourse surrounding lowering cost is a consistently turbulent sea navigated by diverse public and private parties, with the language around drug pricing assuming efforts to curb costs relate to patient costs and access – but not explicitly saying so (and for good reason). Some proposals are government related, such as federal drug pricing proposals. Recent developments are state-level focused closer to home. One such development is the Prescription Drug Advisory Boards, or PDABs.

PDABs are part of state divisions of insurance. Drug pricing efforts, in the general sense, could be a good thing. PDABs are being marketed to the public as a better means to make drugs more affordable for patients. However, the details of the implementation of developing PDABs are wherein lies significant challenges. Overall, the boards focus specifically on the prices of the drugs. However, the focus on pricing is mainly related to what governments, insurance companies, hospitals, and pharmacies are paying for the medications. This purview and the monitored metrics associated with PDABs do not necessarily translate into the actual costs patients pay at the pharmacy counter.

Because these designs are singularly focused on the “cost” to payors, current proposals and initiatives benefit both public and private payors at the expense of the patient access and the provider-patient relationship. It is unacceptable for any planned PDAB activity to disrupt the patient-provider relationship. Community Access National Network (CANN) has consistently opposed any policy initiative that might increase administrative barriers and patient burdens. Two examples are step-therapy and prior authorization. Activities such as these are considered what is known as utilization management. Utilization management helps lower prescription drug spending for public and private payors but creates additional costs for patients financially and logistically, affecting their continuity of care, amounting to a cost burden shift, not a meaningful increase of access to affordable, high-quality care and treatment for patients.

Additionally, the narrow specific focus on the list prices of drugs overlooks essential issues. Lowering the list price for medications can, for example, harm organizations that depend on revenues from the 340B Drug Pricing Program. The 340B program allows safety net clinics and organizations to purchase prescription drugs from manufacturers at a discounted price while being reimbursed by insurance carriers at a non-discounted cost. The surplus enables these entities to provide many services that the low-income populations they serve depend on. This is especially vital to low-income people living with HIV that do not have the means to afford all of their healthcare needs.

It is imperative that PDABs receive input directly from patients and caregivers as well. PDABs are aggregating a large amount of data. However, more of that data needs to include considerations of the patient experience. For example, drug rebate reductions can impact care and support services, such as transportation assistance or mental health services at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). Moreover, there needs to be an examination of the actual pass-through savings to patients. Most importantly, PDABs need to explore how pricing decisions affect patient access. A lower drug list price is not beneficial to patients if it creates or increases administrative burdens or increases costs for patients in other ways outside of paying for the cost of medication.

Most policymakers do not always have robust experience in understanding the nuances of dealing with public health programs, clinics, and populations. This is especially true regarding the marginalized community of people living with or at risk for acquiring HIV, those affected by Hepatitis C, or people who use drugs. PDABS must be held accountable for acquiring anecdotal qualitative and quantitative data regarding patient experience, accessibility, and affordability while developing recommendations related to drug pricing. As it stands, of the states that have implemented a PDAB, none have statutorily mandated metrics monitoring patient experience and access.

Patients, caregivers, and advocates with direct experience and greater understanding of the policy landscape around healthcare access play a vital role in helping to shape legislation and informing proper implementation of programs to meet the goals those programs were “sold” on. If monitored metrics do not consider or reflect patient experiences, then the program is simply not about increasing access for patients.

PDABs, fortunately, do have numerous opportunities for patients, caregivers, advocates, and providers to become involved and to elevate patient priorities over that of other stakeholders. Getting involved and staying involved with a state’s PDAB work is critically necessary to ensure any final work or regulation is patient-focused.

CANN will be present and offering feedback at various PDAB meetings in affected states. The next meeting CANN will be attending is virtual for the state of Colorado, on July 13th at 10am Mountain time. You can register here and participate in ensuring any action taken reflects patient needs.