Beyond the Test: Ensuring Linkage to Care After HIV Self-Testing

HIV self-test kits have emerged as a pivotal tool in the fight against HIV/AIDS, offering a private and convenient method to determine one's status. The World Health Organization endorsed these kits in 2016, marking a significant step in global HIV/AIDS prevention. The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted their importance as traditional testing declined, with the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) emphasizing their role in ensuring continued access to HIV testing.

In the U.S., 14% of the estimated 1.1 million people living with HIV are unaware of their status. Men who have sex with men (MSM) have a particularly high prevalence of undiagnosed men with sero-positive status. Yet, a study in JAMA Network found that only 25.7% of MSM in urban areas had used an HIV self-test. This limited adoption and data indicating that many don't pursue necessary treatment or prevention post-testing, highlights the challenges ahead.

HIV Self-Testing: Nuances and Linkage to Care

HIV self-test kits, endorsed for their easy access to HIV testing, come with detailed instructions for self-administration and result interpretation. However, users are strongly advised to verify their results at a healthcare facility, particularly if they end up with a reactive (“positive”) result.

While the potential of HIV self-testing is evident in its ability to increase the number of people aware of their HIV status, the real challenge lies in ensuring that those who test positive are seamlessly linked to appropriate medical care and support. A study in The Lancet highlighted a significant gap in connecting these individuals to post-testing HIV care. This gap is alarming, considering the importance of early intervention in HIV management, which not only benefits a person’s health but also reduces the risk of transmission.

A systematic review by The Conversation further emphasized this challenge:

There's an 8% increase in users finding an HIV clinic post-testing.

A significant number of users did not initiate HIV treatment or PrEP after self-testing.

Women sex workers were 47% more likely to seek medical care post-testing, yet testing rates among clients of sex workers remained unchanged.

MSM users might engage more in condomless anal sex post self-testing.

One major obstacle in this linkage to care is the lack of localized resources accompanying the test kits. For example, kits from OraSure, a leading manufacturer, provide general post-test advice but often lack specific resources or directions for localized care, leaving people, especially those testing positive, uncertain about their next steps.

To address these challenges, it's crucial to not only link people to care but also ensure they access the necessary treatment and preventive measures. Strategies that have proven effective in bridging care gaps for chronic conditions, like hepatitis B, can be adopted. Leveraging community-based participatory approaches, partnering with community organizations, and implementing robust referral systems can ensure that people receive the essential care and support post-testing.

Benefits, Hurdles, and Real-World Implications of Self-Testing

HIV self-testing offers a private and convenient alternative to traditional methods, addressing barriers such as transportation, stigma, confidentiality concerns, and outdated HIV criminalization laws. A Vital Signs report from 2016 revealed that 38% of new HIV transmissions were from people who were unaware of their status, emphasizing the need for increased testing. The CDC's eSTAMP study found that self-tests doubled the likelihood of MSM identifying new HIV transmissions.

However, challenges persist. Many users, despite recognizing their status, don't or can’t take subsequent necessary steps, such as pursuing HIV treatment or initiating PrEP, as highlighted in The Conversation. Additionally, functional considerations like storage conditions play a role in the effectiveness of self-tests. For instance, the OraQuick test should be stored between 36°F and 80°F, a factor that becomes increasingly relevant in the face of climate change, hot summers, and extended transit times. Similarly, self-testing kits produce physical evidence of screening that needs to be discarded by the person using the test. If that person is in a safe, welcoming situation, storing the test or disposing of the materials from the test might result in risks of experiencing stigma, discrimination, or even harm.

Accuracy in self-testing is paramount. The OraQuick In-Home HIV Test claims over 99% accuracy for negative results and 91.7% for positive ones, though the testing window period can influence accuracy. Users appreciate the autonomy self-testing offers, but it should be part of a broader strategy, complemented by counseling and care linkage and stigma reduction, as emphasized by The Lancet study.

Financial Incentives and Real-Life Implications:

In many studies evaluating the effectiveness and adoption of HIV self-tests, participants were often provided financial incentives to report their test results. This approach ensured a higher rate of result reporting and offered insights into user behavior post-testing. However, in real-life scenarios, such financial incentives are absent. This discrepancy raises concerns about the actual rate of result reporting and subsequent linkage to care when people purchase and use these kits outside of a study environment. Without the motivation of financial incentives, there's a potential risk that some people might not seek further care or counseling after a reactive test, especially if they lack access to localized resources or support systems.

Economic Factors, Barriers, and the Way Forward

Self-testing presents a promising avenue to increase HIV status awareness, but economic and psychological barriers hinder its adoption. The CDC found that 61% of Americans had never been tested for HIV, and less than 30% of those most at risk had been tested in the preceding year.

The CDC's eSTAMP study highlighted the effectiveness of mailing free self-tests, with recipients being more likely to discover their HIV status. Such initiatives are cost-effective, with potential savings of nearly $1.6 million in lifetime HIV treatment costs, as estimated from the eSTAMP trial.

Despite these advantages, challenges like misconceptions about HIV risk, unawareness of self-tests, and cost considerations persist. Additionally, the emotional toll of a reactive result, especially when received alone, is a significant concern. The CDC's efforts to make HIV self-testing more accessible are commendable and addressing these barriers is essential for the initiative's success.

Conclusion

HIV self-testing is a crucial and beneficial tool in our ongoing fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Yet, as with any innovative solution, it's not without its challenges. The true measure of our commitment to Ending the HIV Epidemic lies not just in the tools we develop but in the systems we put in place to ensure their effective use. As we embrace the promise of self-testing, we must also confront the gaps in linkage to care, address the barriers to widespread adoption, and ensure that every person and community, regardless of background, has the support they need post-testing.

We must ask ourselves: Are we doing enough? Are we truly leveraging the potential of these tools to make a lasting impact? The answers to these questions will shape the trajectory of our fight against HIV/AIDS.

Healthcare advancements are made every day, and it's our collective responsibility to ensure these innovations reach and benefit all, especially the most vulnerable among us. As we move forward, let's commit to not only advocating for the tools but also for the comprehensive systems of support that make them truly transformative. Because in the end, it's not just about testing; it's about reducing stigma, saving lives, building healthier communities, and creating a future free from the shadow of HIV/AIDS and that’s worth investing in.

Payer-Denied PrEP Fails Black Women and Marginalized Communities

In the battle against HIV, Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) stands out as a transformative defense, significantly lowering infection risks for those most vulnerable. However, this critical protection remains alarmingly out of reach for many, especially Black women, due to insurance payers' denial of coverage. This systemic neglect transcends a mere healthcare gap; it's a stark reflection of the health disparities that exist in the United States’ healthcare construct.

Recent findings from IDWeek 2023, led by Li Tao, MD, PhD, confirm: obstacles to PrEP, particularly insurance denials, are directly linked to rising HIV diagnoses. The research, spanning January 2019 to February 2023, exposes a distressing reality where people with rejected PrEP claims encountered a 95% higher likelihood of new HIV diagnoses compared to recipients of the medication.

Moreover, delays in PrEP dispensing due to these denials correlated with approximately a 20% increased HIV contraction risk, emphasizing the urgency of immediate PrEP access. This isn't just a postponement; it's a life-threatening denial disproportionately affecting marginalized communities. The study highlights the necessity of prompt PrEP access to prevent new HIV infections, especially for those with rejected or abandoned claims.

Further analysis showed the lowest HIV diagnoses among cisgender men with dispensed claims, contrasting with the highest rates among transgender women and men with abandoned claims. Individuals with sexually transmitted infections in the rejected or abandoned groups also faced elevated HIV diagnosis rates.

These insights "emphasize the dire need to eliminate PrEP access barriers to halt HIV transmission," the researchers concluded.

Empowering People: The Psychological Benefits of PrEP

PrEP's impact extends beyond physical health, offering significant psychological relief. A recent study in Pharmacy Times illustrated that PrEP usage enhances the confidence of people in having safer sex, reducing HIV transmission anxiety. This security is crucial, especially for communities burdened by the constant dread of HIV. It represents not just a medical breakthrough but an empowerment tool, allowing people to regain control over their sexual health without looming HIV fears.

The study, conducted over 96 weeks, encompassed participants from various backgrounds, including men who have sex with men, transgender women, and cisgender women. It found that those on PrEP experienced less anxiety and more comfort during sexual activities, confident in their reduced HIV risk. This mental health benefit was consistent across all groups, highlighting PrEP's universal advantage beyond its physical protective effect.

"PrEP is more than a medical solution; it's a source of hope and assurance for those at elevated risk of HIV," the researchers noted. They suggested that this confidence might encourage adherence to the medication, strengthening prevention efforts.

However, when such empowering medical solutions are restricted, it doesn't just withhold a health service; it robs people of the mental peace that accompanies protection. This added psychological strain compounds the systemic injustices that marginalized communities endure, deepening disparities.

Global Perspectives on HIV Prevention

While the U.S. struggles with healthcare inequities, other countries are advancing in the HIV fight. For example, Australia has made significant strides by implementing a comprehensive HIV prevention approach. A pioneering study in The Lancet HIV demonstrated that integrating HIV treatment-as-prevention (TasP) with PrEP significantly reduced new HIV cases among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM).

This extensive research in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia's most populous states, indicated a substantial rise in the population prevalence of viral suppression, accompanied by a corresponding decline in HIV incidence. The findings advocate for continuous investment in holistic HIV prevention strategies, suggesting that even slight enhancements in treatment and prevention access and adherence can drastically reduce new HIV cases.

However, Australia's success highlights a stark contrast in healthcare access and strategy in the U.S., especially impacting Black women and marginalized communities. The effectiveness of Australia's model stems from its inclusivity, guaranteeing extensive coverage and straightforward access to diagnostic and treatment services. This strategy encompasses not just broad PrEP availability but also a robust focus on TasP, ensuring a high treatment rate among those diagnosed with HIV, thereby lowering their viral load and transmission risk.

In contrast, the U.S. healthcare system's piecemeal strategy, characterized by payer denial for PrEP and other preventive measures, hampers these all-encompassing prevention methods. A Health Affairs study unveiled severe disparities in PrEP access and costs. In 2018, populations such as gay, bisexual, and same gender loving men (GBM), heterosexual women and men, and people who inject drugs encountered the most significant financial barriers. Insurance plays a crucial role in healthcare access, yet it's grossly inadequate regarding PrEP coverage. According to a 2022 study, numerous people encountered administrative barriers, including outright PrEP claim denials. These systemic shortcomings resulted in uncovered costs totaling an astonishing $102.4 million annually, a financial burden that individuals had to shoulder in 2018 alone.

These uncovered costs represent tangible hurdles, keeping potentially life-saving medication inaccessible for many at-risk individuals. The systemic obstacles that Black women face, as outlined in a KFF Health News report, emphasize the grave repercussions of this neglect. Economic challenges, healthcare exclusion, and biased marketing strategies limit PrEP access, leaving this community exposed and overlooked.

The current state demands an immediate reassessment of the U.S. HIV prevention strategy. It's not solely about PrEP accessibility; it's about a comprehensive approach that encompasses effective treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). This strategy involves not just advocating for PrEP insurance coverage but also pushing for extensive healthcare reforms that guarantee all-encompassing coverage, including TasP methods.

Australia's success story provides clear evidence: with the proper dedication and strategic approach, we can substantially lower new HIV transmissions and work towards eradicating the HIV epidemic. However, this achievement requires a collective resolve to seek a healthcare system that serves everyone, not just a privileged minority.

It's time to hold payers and policymakers responsible, to shame them for their role in a system that continues racial and socioeconomic health disparities. Their inaction costs more than money; it costs lives. The U.S. must learn from global success stories and adopt an inclusive, comprehensive HIV prevention strategy that recognizes and caters to the unique needs of all communities, including Black women and other marginalized groups.

The Plight of Black Women

The situation becomes even more tragic when we consider Black women's struggles, especially those identifying as cisgender. Despite bearing a disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic, Black women face numerous systemic barriers, from healthcare alienation and biased marketing to economic hardships, all limiting their PrEP access, as detailed in a KFF Health News report.

One personal story, that of Alexis Perkins as featured in a PBS NewsHour article, illustrates these challenges. Perkins, a 25-year-old nurse, encountered difficulties in obtaining PrEP despite her proactive health efforts. During her visit to her OB-GYN’s office, Perkins sought a prescription for PrEP but encountered several obstacles. The medical assistant who initially greeted her was not only unfamiliar with PrEP but was uncomfortable discussing it. Furthermore, her provider, though aware of PrEP, did not feel confident prescribing it due to a lack of sufficient knowledge about the medication. Her experience reflects a broader systemic problem where healthcare providers often lack PrEP knowledge or are reluctant to prescribe it, failing to meet Black women's health requirements. "It's not something that's being marketed to us," Perkins expressed in the article, indicating the absence of information directed at Black women.

These systemic barriers extend beyond mere neglect; they inflict direct harm. The research points out exclusionary marketing tactics, where PrEP promotional efforts frequently miss Black women, resulting in misunderstandings and unawareness about PrEP's relevance to their lives. This issue is aggravated by the gender disparity in FDA-approved PrEP medications' accessibility, with some treatments tested solely on male participants, restricting their use for women.

While manufacturers have begun addressing these disparities in marketing materials and clinical trial design for emerging therapies, stigma, radical judicial activism, and lack of strengthened or continued investment in public health all threaten our ability to meet our goals in Ending the HIV Epidemic.

Economic barriers, more common among Black communities, exacerbate these challenges, making consistent PrEP usage difficult. The necessity for regular medical appointments and HIV testing, along with high initiation costs and logistical hurdles, presents significant obstacles. As the PBS article elaborates, these economic and logistical barriers, particularly for those in poverty, are daunting and often insurmountable, barring Black women from the healthcare they deserve.

Addressing this healthcare inequality demands a comprehensive strategy. Economic and social empowerment, community-focused health campaigns, and policy and research initiatives are essential. Improving access to quality employment, healthcare, and stable housing can empower Black women to make informed health decisions. Customized health messaging and community dialogues, as well as policy and research efforts like those by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Gilead Sciences, are vital steps toward closing these gaps.

Alexis Perkins' story is not unique; it reflects the experiences of many individuals navigating a healthcare system that consistently fails them. As we face these harsh truths, we must acknowledge that this crisis goes beyond medicine; it's a moral issue. The barriers preventing access to PrEP for the most at-risk communities are not mere oversights; they are expressions of a societal hierarchy that deems certain lives less worthy.

This is more than a health disparity; it's a measure of our societal values. Will we maintain a system that actively undermines the health and futures of its most vulnerable? Or do we possess the collective bravery to demand change?

Change is achievable; it's been proven. Nations like Australia have adopted inclusive, forward-thinking, and compassionate public health policies, dramatically reducing HIV transmission and new diagnoses. Their methods show that with sufficient commitment, we can revolutionize healthcare delivery.

Reflecting on the stories of people like Alexis Perkins, let's contemplate our role in this narrative. Will we be passive observers in a system that discriminates and excludes, or will we become advocates, championing a future where healthcare is a right, not a privilege determined by socioeconomic status? The decision is ours, and it's one we must make now. Because with every moment we delay, every moment we choose inaction, we become silent co-conspirators in a system that tallies casualties instead of champions. In a country that boasts freedom and justice for all, how long will we allow these injustices to determine who gets to live, prosper, and contribute to our society?

Considerations for Hepatitis C Vaccine in HIV-HCV Co-Infected Populations

The interplay between groundbreaking research and its real-world application can shape the trajectory of entire communities. Once of the most evident place we see this is in the realm of HIV-HCV co-infection. As we stand on the precipice of breakthroughs in Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) vaccine development, the unique challenges posed by HIV-HCV coinfection come into sharp focus, reminding us of the urgency and significance of our endeavors.

Understanding the Landscape of HIV-HCV Coinfection:

HIV and HCV coinfection represents both a medical challenge and a reflection of broader societal issues searching for policy solutions. These viruses mainly impact marginalized communities, highlighting deeper socio-economic disparities. The combination of HIV, which taxes the immune system, even when well-controlled, and HCV intensifies health risks, such as liver diseases, emphasizes the need for effective interventions like a preventive HCV vaccine. Beyond the medical perspective, societal barriers like stigma, payer barriers, and limited healthcare access further complicate the issue. Recent vaccination studies, including those for COVID-19 and Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) among people living with HIV (PLWH), underscore these challenges and the necessity for tailored strategies. To comprehensively address HIV-HCV co-infection, a holistic approach that considers both medical and societal aspects is essential.

Drawing Parallels: Vaccination Lessons for HIV Patients:

The vaccination experiences of PLWH, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlight the need for tailored strategies. While HIV patients were prioritized due to potential severe COVID-19 risks, vaccine efficacy varied based on individual immune responses, suggesting the potential need for boosters. Similarly, the Hepatitis B vaccination journey revealed that many PLWH had suboptimal responses to the standard vaccine. However, alternative, additional, or re-administration dosing regimens emerged as a promising solution. As we approach HCV vaccine development for people with co-occurring conditions, these experiences and the data-driven developments originating from them provide invaluable insights to anticipate challenges and innovate solutions.

Special Considerations for Vulnerable Populations:

Equitable policy and programmatic design in public health ensures everyone has access to optimal healthcare, yet societal barriers often sideline certain groups. Incarcerated people face challenges like close-quartered living and limited healthcare access, amplifying the transmission of illnesses like HIV and HCV. Tailored strategies, informed by COVID-19 vaccination efforts in prisons, such as on-site clinics, can improve vaccine uptake. People experiencing homelessness, battling issues like unstable housing and societal stigma, benefit from strategies like mobile clinics and community collaborations, as seen with HBV vaccinations. Building community trust, especially for populations with historical mistrust, is vital. Addressing HIV-HCV coinfection requires an inclusive, trust-centric approach, ensuring no one is overlooked.

Parallels with Mpox Vaccine: Addressing Vulnerable Populations

The U.S. Mpox outbreak in 2022 highlighted health disparities, especially among people experiencing homelessness, LGBTQ+ persons, and people of color. Mpox's transmission and significant impact on gay, bi sexual, and same gender loving men (GBSGLM), including those living with HIV, mirrors challenges with HIV-HCV co-infection.

The outbreak revealed health inequity issues, such as stigma and misinformation, exacerbated by the disease's former name "monkeypox." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Mpox Vaccine Equity Pilot Program and Chicago Health Department's community-centric strategies provided insights for HIV-HCV coinfection management. Key takeaways included:

Community Engagement: Engage with affected communities, fostering trust through tailored programs and partnerships. Ready availability and responsiveness were critical to earned trust among affected communities.

Combatting Stigma: Deliver clear messages to dispel myths, ensuring vaccine uptake.

Vaccine Accessibility: Emphasize genuine accessibility, especially for marginalized groups, inspired by the Mpox Vaccine Equity Pilot Program.

Addressing HIV-HCV Co-infection in Vulnerable Groups:

Equity is vital in managing HIV-HCV co-infection, with incarcerated persons and populations experiencing homelessness and housing instability demanding special focus.

Incarcerated Populations: Prisons, due to their close confines and shared activities, are hotspots for disease transmission. While confinement offers some healthcare delivery opportunities, many lack comprehensive or personalized care, and most-notably, provide a microcosm of healthcare failures affecting surrounding communities. Identifying cost-effective program designs which address these disparate would prove beneficial for communities writ-large. Similarly, ensuring post-release care continuity is essential.

Homeless Populations: The transient nature of homelessness poses healthcare consistency challenges. Drawing from smallpox vaccine strategies, mobile clinics and community partnerships are effective. Building trust through tailored campaigns and community collaborations is crucial.

General Considerations: Skilled staff, robust data management, and inter-agency collaborations are essential for effective vaccination campaigns. Sufficient appropriations are required in order to build and maintain the missions of public health departments.

By addressing these populations' unique challenges, we can create an inclusive HIV-HCV coinfection strategy.

Future Medical Considerations:

The evolving nature of medical science presents new challenges and questions. The relationship between HIV and HCV may necessitate a tailored vaccine approach. Given experiences with COVID-19 and HBV vaccinations, how can we optimize the HCV vaccine for PLWH? Are there specific strategies to enhance its efficacy?

Public trust in health institutions remains fragile and highly politcized. How can we effectively communicate an HCV vaccine's importance and safety? How can we rebuild community trust?

Globally, ensuring the HCV vaccine's equitable access, especially in vulnerable populations with significant HIV-HCV co-infection risk, is a challenge. Can we learn from other vaccine distribution programs to strategize for HCV?

Urgent Considerations for HIV-HCV Coinfection's Future:

As we navigate the complexities of HIV-HCV coinfection, several pivotal questions arise, guiding researchers, policymakers, and healthcare professionals:

Vaccine Efficacy: Given varied vaccine responses in HIV patients, such as with COVID-19 and HBV, how can we optimize the HCV vaccine's effectiveness?

Access and Trust: How can we promote equal access, especially for vulnerable groups, and rebuild public trust?

Global Collaboration: How can we ensure global HCV vaccine access and which partnerships are essential?

Learning from History: Using insights from the U.S. Mpox outbreak, how can we better anticipate and manage health crises?

Policy Evolution: How can we swiftly incorporate evidence-based discoveries into health policies?

Actionable Recommendations for HIV-HCV Management:

To effectively combat HIV-HCV coinfection, we should consider:

Vaccination Strategies: Given varied responses among PLWH, explore frequent dosing, boosters, or double-dosing for the HCV vaccine, as seen with HBV and COVID-19.

Monitoring: Implement regular health assessments post-vaccination and periodic antibody and viral load tests.

Policy and Awareness: Prioritize coinfected individuals in vaccine rollouts, ensure accessibility, and launch awareness campaigns.

Collaborative Efforts: Foster interdisciplinary and global collaborations to holistically address HIV-HCV coinfection.

Addressing Current Deficiencies in Access: Despite curative therapies for HCV being readily accessible for more than decade, HCV remains a pressing public health concern in the United States. Effective vaccine distribution will hinge on addressing the challenges identified by these findings.

By strategically planning with these considerations in mind, we can create a comprehensive plan, prioritizing the well-being of those impacted by HIV-HCV co-infection.

Streamlining Vaccine Delivery and Building Trust in Healthcare

Efficient Vaccine Delivery: Successfully delivering vaccines for HIV-HCV co-infection requires more than just the vaccine. It's about a blend of skilled staff, efficient processes, and the right infrastructure:

Continuous Training: Ensure healthcare professionals are updated on the latest in vaccine administration for coinfections.

Resource Allocation: Balance routine healthcare with specialized vaccine campaigns, especially in resource-limited settings.

Infrastructure Upgrades: Enhance facilities, considering temperature-controlled storage and patient comfort, especially in remote areas.

Addressing Staffing Issues: Bridge the gap in healthcare professional shortages to ensure comprehensive care.

Workflow Efficiency: Use technology and process improvements for a seamless patient experience.

Community Health Worker Integration: Utilize their insights and community rapport to enhance healthcare delivery.

Feedback-Driven Improvements: Create a feedback-rich environment for continuous workflow enhancements.

Rebuilding Trust in Public Health: Trust is the bedrock of public health success, especially in the context of HIV-HCV coinfection:

Recognize Historical Mistrust: Address and make amends for past skepticism, especially among marginalized groups.

Combat Misinformation: Proactively counter myths about vaccines and transmission in the digital age.

Cultural Outreach: Use tailored messages and collaborate with community leaders for effective health drives.

Prioritize Transparency: Regularly update and demystify vaccine processes to foster trust.

Empathetic Engagement: Address vaccine hesitancy with understanding and compassion.

Collaborative Efforts: Partner with trusted community figures to amplify public health messages.

Feedback and Accountability: Implement public feedback mechanisms and act on them to reinforce trust.

In addressing HIV-HCV co-infection, both operational efficiency and trust-building are paramount. Together, they form the pillars of a comprehensive approach to public health challenges.

Conclusion:

Exploring the complexities of HIV-HCV coinfection reveals the depth of challenges and potential of modern healthcare. Each revelation, whether from studies on COVID-19, HBV, or HCV, not only highlight the gaps in our current understanding but also illuminates potential pathways forward. These insights should serve as guiding lights, directing our strategic development and interventions in the context of HIV-HCV co-infection.

However, our journey through this complex landscape is not solely guided by scientific discoveries. Central to our mission is a profound commitment to humanity and equity. It's a pledge to ensure that every individual, regardless of their background or circumstances, receives optimal care. From vulnerable groups, such as people experiencing homelessness or incarcerated persons, informed by lessons from the U.S. Mpox outbreak, to those in remote areas with limited healthcare access, our overarching goal remains steadfast: no one should be left behind.

By fostering collaboration across sectors, continuously updating our knowledge, ensuring investment in public health, and placing community engagement and trust at the forefront of our efforts, we can carve out a promising path. A trajectory that not only addresses the immediate challenges of HIV-HCV coinfection but also sets the stage for a healthier, more inclusive future for all affected individuals.

Upper-Payment Limits; Drug "Affordability" Boards Risk Medication Access

The opinion piece, authored by Jen Laws, CANN’s President & CEO, originally published in the September 2, 2023, print edition of the Denver Post. CANN will be hosting a free “PDAB 101” webinar for patients, advocates, and all public health stakeholders on November 1, 2023. Pre-registration is required. Register by clicking here.

To successfully combat the HIV epidemic and defeat other chronic conditions, patients must have uninterrupted access to the most effective medicines recommended by their doctors. As efforts to ensure patients can access their medicines are being defined in the public sphere, many state legislatures continue to advance policies and proposals focused on addressing patient affordability challenges.

However, many such actions fail to address high out-of-pocket costs and instead focus on lowering costs for other stakeholders within the health care system, like lowering costs and increasing profits for health insurers neglecting the patients they were intended to protect.

In Colorado and several other states across the country, lawmakers have empowered Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) to address the rising costs that patients pay for prescription medicines. PDABs have the authority to select and review drug list prices and can recommend policies for drugs deemed "unaffordable." These list prices aren't something patients generally pay, rather we pay co-pays or are able to manage costs with patient assistance programs.

Despite this, one such policy being considered by the Colorado PDAB and similar boards in other states is an upper-payment limit (UPL). A UPL is a payment limit or ceiling that applies to all purchases and payments for certain high-cost drugs and does not necessarily translate into a "cost limit" for patients.

When UPLs are set, reimbursement rates are lowered for hospitals or clinics giving them less incentive to purchase specific drugs even though it may be the most effective medication to help a patient manage a chronic condition. When reimbursement rates are lowered through a UPL, it can also lead to barriers to biopharmaceutical companies investing in and supplying new innovative medicines to health facilities, making it difficult for doctors to prescribe treatments they think are best suited for their patients. While well intentioned, patients often bear the brunt of the challenges with such policies.

The impacts of the UPL process are only compounded when we consider the potential impact on the 340B Drug Pricing Program, a federal safety-net program that helps health facilities serve low-income and uninsured patients by offering them discounted drugs. Under the program, qualified clinics and other covered entities buy treatments at a discount to help treat vulnerable patients and get to keep the difference between the reimbursement rate and the discounted price leveraging those dollars to provide needy patients with medications and care they might not otherwise be able to afford.

Under a UPL, health facilities such as hospitals or clinics will receive lower reimbursements for prescribed treatments and therefore generate fewer dollars to support patients and the care we need to live and thrive. If the PDAB sets restrictive UPLs for drugs for chronic conditions like HIV, health facilities and the health professionals tasked with providing care will be faced with the decision to potentially stop prescribing these medicines and face having to cut support services that patients have come to rely on.

At a recent meeting of Colorado PDAB stakeholders, following the board's unanimous approval of the list of drugs eligible for an affordability review process, I voiced concerns about the approach to determining the value of lifesaving treatments for patients living with or at risk for HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and other complex conditions. My concerns have only grown since, most recently, the state PDAB selected five drugs to undergo a formal affordability review including a treatment for HIV.

Many patients and other stakeholders have raised alarm to other drugs that are now subject to review to treat complex conditions such as psoriasis, arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and cystic fibrosis. The implications of the Colorado drug "affordability" board's recent actions on patient access are grave and set a dangerous precedent. Ten states including Colorado have already established PDABs, and many others are following suit.

Those support services and continuity of care are critical to empower communities and improve the quality of life for people living with and managing conditions like HIV and hepatitis C. Despite the PDAB being "sold" to the public as a measure to improve patient experiences and access to care, the current model fails to prioritize patients at all.

Colorado is home to more than 13,000 people living with HIV and has been at the forefront of combating the disease. This year, state lawmakers advanced model legislation that protects patients' access to HIV prevention medication. However, the recent actions from the drug "affordability" board and short-sighted policies like the UPL process or mandatory generic switching could derail progress toward ending the HIV epidemic.

Price controls are, and will continue to be, a short-term, short-sighted "fix" with long-term consequences for patients living with chronic conditions. Policy efforts to address affordability must prioritize patient access and the ability for doctors to prescribe effective treatments. Colorado's PDAB, as it currently stands, falls short of that.

Alcohol Use Does Not Harm DAA Efficacy, Yet Payer Barriers Persist

In healthcare, the interplay between perceptions and policies can sometimes adversely affect the very individuals they intend to benefit. One such area of contention is the perceived impact of alcohol use on the effectiveness of treatments for hepatitis C Virus (HCV). A recent study, published in JAMA Network Open and spotlighted by MedPage Today, led by Christopher T. Rentsch, PhD, and co-authored by Emily J. Cartwright, MD, explored this relationship. Their findings were clear: alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (AUD) did not diminish the odds of achieving a sustained virologic response with Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) therapy for chronic HCV infection.

Yet, despite such evidence, certain clinicians still hesitate or even refuse to administer HCV therapy to patients who consume alcohol. Furthermore, some payers mandate alcohol abstinence as a precondition for reimbursing DAA therapy for HCV. This stance becomes even more alarming in light of the Center for Disease Control & Prevention's (CDC) recent data, which shows a staggering 129% surge in reported cases of acute hepatitis C since 2014. It's imperative that we prioritize evidence over misconceptions, especially when lives are at stake.

The NIH's Perspective

A study supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) echoes these findings, revealing that individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) are less likely to receive antiviral treatments for hepatitis C. Despite current guidelines recommending such treatment irrespective of alcohol use, the study, led by scientists at Yale University, found that those with AUD, even if they were currently abstinent, were less likely to receive curative DAA treatment for hepatitis C within one or three years of diagnosis compared to those without AUD. This treatment gap, attributed to stigma around substance use and concerns about treatment adherence, underscores the need to address these disparities, especially among those with AUD.

The Case for Change

The implications of these studies are clear: policies need revision. Evidence-based policies in healthcare are paramount. Denying HCV patients access to DAA therapy based on their alcohol consumption habits is not only unwarranted but also counterproductive. As the study's authors have highlighted, such restrictions could pose unnecessary barriers for patients and hinder efforts to eliminate HCV.

Both state-specific policies and national guidelines, like those from The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), need to evolve in light of these findings. Healthcare providers, policymakers, and advocacy groups have a pivotal role in driving this change, ensuring that all HCV patients, irrespective of their alcohol consumption habits, have access to the best possible care.

Charting a Path Forward

The revelations from these studies underscore more than just the need for policy adjustments; they challenge our collective commitment to championing evidence-based healthcare. In an era where misinformation can easily cloud judgment, it's crucial that treatments for HCV are not just theoretically available but are genuinely accessible to all, regardless of their alcohol consumption habits.

The findings from both the NIH and JAMA studies don't merely point out gaps; they expose deep-rooted systemic issues. Current policies have not adequately addressed the needs of HCV patients, and there's a pressing need for more inclusive guidelines.

To transform this call to action into tangible progress, we must:

Reassess and Revise Existing Policies: Ensure that guidelines, especially those from influential bodies like AASLD, are updated in line with the latest scientific evidence, removing any unwarranted barriers related to alcohol consumption. As demonstrated by the efficacy of the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation’s (CHLPI) work in assessing and breaking down barriers to curative DAAs in Medicaid programs, further work must be done to break these payer-based barriers to care in private and employer sponsored plans.

Strengthen Advocacy and Awareness: Engage with healthcare providers, policymakers, and patients to spread awareness about the non-impact of alcohol on DAA therapy's efficacy, countering prevailing misconceptions.

Promote Continuous Research and Dialogue: Encourage further studies and maintain an open dialogue with all stakeholders to continuously refine our understanding and approach to HCV treatment.

The conclusions drawn from these studies underscore the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead of us. As the research emphatically states, alcohol consumption should not be a barrier to HCV treatment. Such restrictions are discriminatory in nature and threaten efforts in the fight to eliminate HCV. With evidence-based policy decisions and unwavering dedication, we can eliminate the barriers and ensure access to curative HCV treatment.

Unveiling Disparities: OIG Report on HIV Care in Medicaid

A recent report by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) unveiled a startling revelation: one in four Medicaid enrollees with HIV may not have received critical services in 2021. At a time when healthcare systems worldwide were grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, these findings highlight the compounded struggles faced by People Living with HIV (PLWH) in accessing essential care.

Beyond safeguarding the health of PLWH, viral suppression plays a pivotal role in curbing HIV transmission, a critical metric in the public health effort to end HIV. In alignment with HHS guidelines, achieving consistent viral suppression necessitates three foundational elements: routine medical consultations, ongoing viral load assessments, and unwavering commitment to ART regimens.

Unveiling the Care Gaps

The OIG's analysis reveals pressing challenges within our system:

Out of the 265,493 Medicaid enrollees diagnosed with HIV, a startling 27% were missing evidence of receiving at least one of the pivotal services last year.

10% were missing evidence of medical visits, and 11% were missing evidence of an ART prescription, raising concerns around disease progression and higher incidence of AIDS diagnosis, increased risk of transmitting the virus, and developing antiviral resistance.

The most pronounced gap? Viral load tests. A staggering 23% of enrollees lacked evidence of even a single viral load test in 2021. This absence not only impedes clinicians from making informed decisions but also hampers our collective ability to monitor and respond to the evolving nature of the HIV epidemic.

Perhaps most concerning is the fact that more than 11,000 of these enrollees didn't have evidence of availing any of the three critical services. This is not just a statistic; it's a reflection of real individuals, facing amplified health risks due to system inadequacies.

Jen Laws, CANN's President and CEO, poignantly remarked, "Medicaid represents the greatest public program coverage of PLWH. It also represents the greatest public program coverage of people at risk of acquiring HIV. Medicaid compliance and efficacy is critical to Ending the HIV Epidemic and this report has identified gaps where states have failed to meet their obligations to Medicaid beneficiaries and where CMS has failed to ensure compliance. We must do better if we are going to reach our public health goals."

The report underscores stark disparities in care access between Medicaid-only and dual-eligible enrollees (those with both Medicaid and Medicare). Specifically, Medicaid-only enrollees were three times more likely to lack evidence of any of the three critical services compared to dual-eligible enrollees, with 6% of Medicaid-only enrollees missing out, as opposed to just 2% of the dual-eligible group. Such disparities might stem from various factors, including Medicare's higher fee-for-service rates and the observed long-standing adherence patterns among older adults who have had HIV for prolonged periods.

State-wide Disparities: A Complex Landscape

The disparities in HIV care access across states offer both a grim reality check and a clarion call for systemic reform. Drawing from the OIG report, certain states, notably Arizona, Arkansas, the District of Columbia, and Utah, have alarmingly high proportions of Medicaid-only enrollees without evidence of at least one of the three critical services. For instance, Utah stands out with a staggering 87% of such enrollees missing out on essential care. These aren't just numbers; they represent real individuals grappling with a system that's failing them.

Conversely, some states demonstrate better compliance and efficacy in delivering HIV care, which suggests potential models or strategies that could be emulated across the board. However, the stark variability across states points to the undeniable influence of state-specific policies, the quality of local HIV care infrastructures, and broader challenges associated with healthcare access.

State agencies clearly have much work ahead. These disparities not only indicate potential inefficiencies or gaps in policy implementation but also suggest a pressing need for introspection and reform at the state level. Coupled with challenges in the broader Medicaid system, there's a compelling case for a comprehensive overhaul.

The onus is on both state agencies and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to rise to the occasion. The disparities, as evidenced in the report, necessitate a deep dive to understand the underlying causes. Is it a matter of policy misalignment, funding constraints, administrative challenges, or a combination thereof?

For instance, the significant variation in care access among dual-eligible enrollees, ranging from 9% to 53% across states, speaks volumes about the discrepancies in policy implementation and oversight. It's vital to pinpoint these issues, develop tailored interventions, and ensure that every Medicaid enrollee, irrespective of their state, receives the essential services they need.

The Pandemic's Shadow

The COVID-19 pandemic exerted immense pressure on healthcare systems, with profound implications for HIV care. The OIG report highlights the challenges faced by Medicaid enrollees with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. A significant finding from the report is the notable deficiency in viral load tests among these enrollees. This underscores the need for healthcare systems to effectively manage and prioritize essential services, even amidst broader healthcare crises. The report serves as a reminder of the importance of consistent and uninterrupted care for conditions like HIV, even when healthcare systems face external pressures.

Steering Towards a Brighter Future

Addressing the glaring disparities laid out in the OIG report goes beyond mere policy recalibration; it challenges our collective resolve to uphold equitable healthcare. In the shadow of the pandemic's aftermath, it's imperative that essential services for PLWH are not just nominally available but are genuinely accessible.

The OIG report's findings don't merely spotlight discrepancies; they highlight systemic lapses. States have fallen short in fulfilling their obligations to Medicaid beneficiaries, and the CMS has not adequately ensured compliance.

To translate this call to action into meaningful change, it's essential to:

Strengthen state-level accountability frameworks to ensure Medicaid obligations are met comprehensively, particularly among states utilizing Managed Care Organizations – ensuring those contracted for-profit insurance companies are meeting their contractual obligations to states. The tools for accountability already exist within these contracts, they merely must be used.

Bolster CMS oversight mechanisms, driving proactive interventions that hold states to account and rectify compliance lapses.

Engage in continuous dialogue with stakeholders, including healthcare providers and beneficiaries, to identify and remedy bottlenecks in care access.

The findings from the OIG report serve as a stark reminder of the work ahead. As Jen Laws aptly states, "We must do better." HIV advocates should consider assessing our engagement with their state Medicaid programs and look for opportunities to act, akin to our engagement Ryan White programs. With concerted efforts, policy reforms, and collective commitment, we can bridge the gaps and ensure comprehensive care for all PLWH.

340B Hypocrisy: The Inconvenient Truth Behind Why We Need to Reform This Vital Safety Net Program

Brandon Macsata is the CEO of ADAP Advocacy. Jen Laws is the CEO of Community Access National Network.

The 340B Drug Pricing Program (“340B”) is probably one of the most transformative public health programs providing lifesaving supports and services to people living with HIV in the United States, second only to the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (“RWHAP”). As such, rigorous debate about the future of the program is not only healthy, but it is also paramount to its success. As patients (and patient advocates), it is our responsibility to demand accountability, transparency, and stability. There is universal agreement about the vital role 340B plays in improving access to healthcare. But for many – including ADAP Advocacy and the Community Access National Network – we contend that the program could be doing more…and better! The focus of the program should be on the patients, and not the Covered Entities, medical or service providers, or any other business enterprises making lots of money off it. That is the inconvenient truth behind why we need to reform this vital safety net program.

Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) is a Drug Pricing Program established by the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992. That year, Congress struck a deal with pharmaceutical manufacturers to expand access to care and medication for more patients; if pharmaceutical manufacturers wanted to be included in Medicaid’s coverage, then they’d have to offer their products to outpatient entities serving low-income patients at a discount. The idea was brilliantly simple. Drug manufacturers could have a guaranteed income from participation in the Medicaid program and Covered Entities could have guaranteed access to discounted medications. Congress set-up a payment system by way of rebates and discounts affording certain healthcare providers a way to fund much needed care to patients who could not otherwise afford it.

“…to stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.” H.R. Rep. No. 102-384(II), at 12 (1992)

THAT is the legislative intent behind 340B. THAT is where some of us want to return 340B’s focus. THAT is why reform is coming!

Ironically, critics of the 340B reform movement – often motivated by self-preservation and protecting their ever-expanding budget and geographic footprint – are quick to attack the idea of the need for reforms. Sadly, they’re also quick to turn their criticism into personal attacks, including questioning the intentions, morals, and character of the people supporting reform. They charge, using Inspector Clouseau “gotcha” style rhetoric, that we’re in the “pockets” of the drug manufacturers because we accept their money to help with our patient advocacy and education (yet there is no “gotcha”, since this information is quite publicly available on our websites, annual tax returns, Guidestar, as well as frequent public commentary).

Isn’t it funny how the “gotcha” mentality cannot accept the obvious, that maybe our interests align with the drug manufacturers because it is in the best interest of patients. Drug manufacturers make products patients want and need. Ensuring funding flows in a way that expands patient access to medications does indeed benefit both patients and the drug manufacturers. It should be noted, this criticism tends to also neglect mentioning the interests of the entities challenging reform: anti-competitive consolidation among hospitals and pharmacies (leaving whole areas without services), increasing profits, paying for salaries unrelated to healthcare, and increasing administrative salaries are all excellent examples of why we’re left asking “Who is actually benefiting from this program?”

The truth of the matter is, aside from a growing list of patients, patient advocacy organizations, and drug manufacturers, there is a growing chorus calling for reform. Academia wants it (NEJM, Penn LDI, USC Schaeffer), economists want it (Nikpay, Gracia), national trade associations want it (NACHC, NTU), policy think tanks want it (CMPI, NAN), and even multiple news media outlets are suggesting it (Forbes, NYT, WSJ). Local activists are also increasingly fed-up with what they’re witnessing (Dinkins, Feldman, Winstead).

Dr. Diane Nugent, Founder & Medical Director of the Center for Inherited Blood Disorders, recently noted an opinion piece in the Times of San Diego, “A September 2022 analysis by the Community Oncology Alliance revealed that some hospitals participating in 340B price leading oncology medications nearly five times more than the price they paid. Another study found that hospital systems charge an average of 86% more than private clinics for cancer drug infusions.”

But speaking of deep pockets, isn’t it also an inconvenient truth that the very folks fighting reform, and fighting improving the program so patients can benefit more directly from it, are the same folks financed by big hospital systems, and mega service providers abusing 340B intent?

A question often asked by advocates learning about 340B: “So, exactly how much money are we talking about here?”

Well, we don’t really know…sort of. For Federal Grantees covered under 340B, their grant contracts require accounting of 340B rebates as part of their programmatic revenues. Those revenues are required to be re-invested in the program, which generated the income. This level of transparency is pretty much a “gold standard” that other Covered Entities (less maybe hemophiliac centers) in the 340B space are required to meet. That’s part of why we, and other advocates, are calling on minimum reporting requirements for hospitals, contract pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers (insurers covering medications) to begin providing some data. Clearing up the murkiness, if you will. What we do know is drug manufacturers reported more than $100 BILLION in 340B-related sales last year.

That’s concerning especially because “charity care” is declining and medical debt is a growing issue for more and more patients and their families. The Affordable Care Act mandated “charity care”, or “financial assistance”, to be offered by non-profit hospitals seeking to qualify as 340B entities but did not place any definitions behind the mandate, including any “floor” of how much charity care a hospital has to offer.

Now, in all rhetoric opposing any type of transparency in 340B, hospitals tend to conflate their “uncompensated care” and “unreimbursed care” or “off-sets” for public health programs – these don’t necessarily reflect any “charity” being provided to patients. These things should be separated when considering what benefit hospitals provide a community. And under that lens, things get kind of ugly with far too many of the 340B hospitals reporting providing less than 1% of their operating costs as charity. When reviewing how much hospitals write off in bad debt, or going after patients who can’t afford care, often far exceeding those charity care levels, we’re left asking if the “non-profit” designation is really a declaration of concentrating “profits” by way of salaries to top executives rather than formal shareholders?

That bad debt shows up for patients as medical debt. And we need to be very specific here: according to the Urban Institute, some 72% of patients with medical debt owe some or all of that debt to hospitals. Meaning, what we call medical debt is really hospital debt. The situation is unarguably bad. This year alone the Los Angeles County Office of Public Health issued a report outlining for policymakers the role and responsibility hospitals have in driving medical debt and how increasing charity care might stem this problem.

As patients, and frankly as patient advocates who represent thousands like us, medical debt isn’t an issue that can be swept under the carpet. Entire communities avoid necessary care to protect their financial interests. We’ve personally watched our friends open GoFundMe accounts to cover medical expenses. We’ve helped our loved one’s cover food and light bills to not miss a medical bill. We also well recognize how negative credit reporting from medical debt can hurt people from getting rental housing or a car loan, or even simple necessities. And when thinking about how much we don’t know about what’s behind that $100 billion price tag, the fact that patients face these concerns on the regular is pretty obscene.

We do know there are plenty of good actors in the 340B space. Particularly, Federal Grantee Covered Entities, like Ryan White Clinics and AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs). And we know they’re generally great actors because of that transparency in reporting and the oversight offered by their grant contracts. Ultimately, we’re not necessarily asking for a whole lot more than that for literally everyone else who stands to make a buck in the chain between drug manufacturers and patients. Indeed, that trust on Federal Grantees, particularly Ryan White Clinics and ADAPs, is part of why drug manufacturers restricting 340B sales held a carve out for these Federal Grantees. (To be fair and without much public fanfare, years ago, we – as in ADAP Advocacy and CANN – helped to negotiate these carve-outs as part of our advocacy. Our relationship with drug manufacturers isn’t a one-way street as detractors might try and sell you on.

$100 billion is a lot of money! Is it too much to ask, “Why aren’t patients benefiting more directly from this ever-growing healthcare program?” Facts show that 340B revenues are soaring year after year, yet against the grim backdrop of consistently declining charity care in the impoverished communities needing the most help. To make matters worse, rising medical debt is crushing families. Patients deserve better. People living with HIV who depend on the RWHAP and 340B deserve better! And that is why we need reform.

Read our policy reform suggestions here.

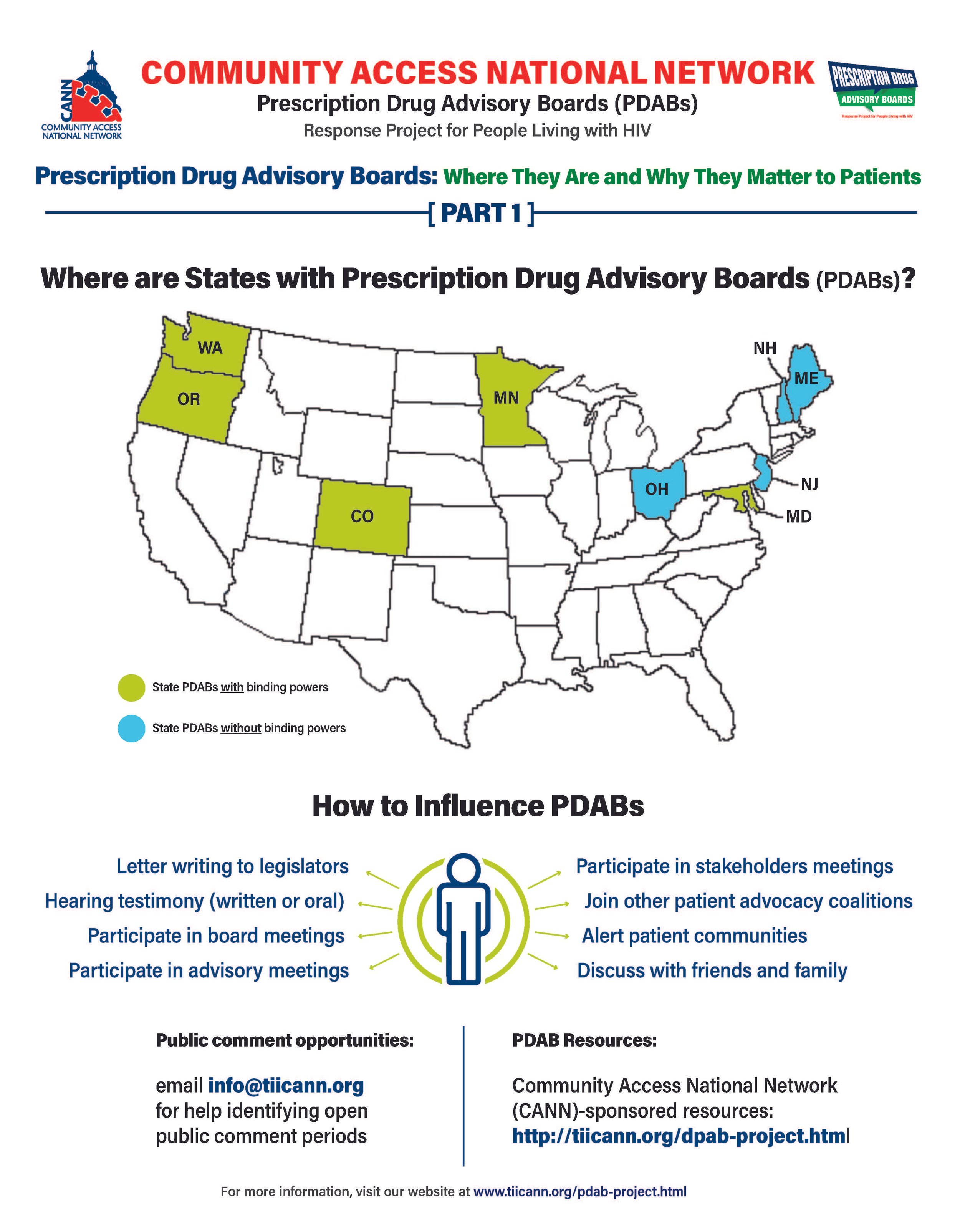

Prescription Drug Advisory Boards: Who is Impacted and How to get Involved

The prescription drug advisory board (PDAB) train keeps chugging along. Presently, there are nine (9) states that had, have or are in the process of enacting PDAB legislation: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maryland, and Maine. Ohio, it would seem, has abandoned their PDAB efforts. Their geographical variance reflects the diversity of their structures. Some of the boards have five members, and some have seven. While all are appointed by the governor, they differ regarding which departments they are associated with. For example, Colorado’s is associated with the Division of Insurance, and Oregon’s is associated with the Department of Consumer and Business Services.

The assortment of structure does not stop at department association. The number of drugs to be selected annually for review also varies, such as Colorado with five and Oregon with nine. Even the number of advisory council members lacks consistency. The New Jersey DPAB advisory council has twenty-seven (27) members, while Colorado’s has fifteen (15). Inconsistency in structure means inconsistency in operations. Thus, the help or harm patients ultimately receive will vary drastically from state to state. The most important differences are the powers bestowed upon the various DPABs. In addition to shaping many policy recommendations, five (5) currently have the ability to enact binding upper payment limit (UPL) settings: Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Maryland, and Minnesota.

An upper payment limit sets a maximum for all purchases and payments for expensive drugs. By setting UPLs for high-cost medications, improved ability to finance treatment equals greater access to high-cost medicines. A UPL sets a ceiling on what a payor may reimburse for a drug, including public health plans, like Medicaid.

Patients, advocates, caregivers, and providers are concerned about PDABs because the outcomes of theory versus practice can have dire consequences. Theoretically, PDABs should reduce what patients spend out of pocket for medications and lower government prescription drug expenditures. However, the varied ways different PDABs are set to operate could jeopardize goals. Focusing on lowering reimbursement rates could affect the funds used as a lifeline by organizations benefiting from the 340B pricing program even while not meaningfully reducing patient out-of-pocket costs. If reimbursement limits are set too low, those entities will have drastic reductions in the funding they use for services for the vulnerable populations they serve. UPLs could ultimately increase patients' financial burden if payers increase cost-sharing and change formulary tiers to offset profit loss from pricing changes or institute utilization management practices like step-therapy or prior authorization. Increasing patient administrative burden necessarily decreases access to medication. When patients are made to spend more time arguing for the medication they and their provider have determined to be the best suited for them, rather than simply being able to access the medication, the more likely patients are to have to miss work to fight for the medication they need or make multiple pharmacy trips – or suffer the health and financial consequences of having to “fail” a different medication first. PDAB changes could affect provider reimbursement, which could be lowered with pervasive pricing changes. Decreased provider reimbursement could result in additional costs being passed onto patients or, in the situation of 340B, safety-net providers, reduce available funding for support services patients have come to rely upon.

The divergent factors that different PDABs use for decision-making are of concern as well. It is not enough to just look at the list price of drugs and the number of people using them. For example, some worthwhile criteria for consideration of affordability challenges codified in Oregon’s PDAB legislation are: “Whether the prescription drug has led to health inequities in communities of color… The impact on patient access to the drug considering standard prescription drug benefit designs in health insurance plans offered…The relative financial impacts to health, medical or social services costs as can be quantified and compared to the costs of existing therapeutic alternatives…”. But few of these PDABs consider payer-related issues like limited in-network pharmacies, discriminatory reimbursement, patient steering mechanisms, or frequency of utilization management as hindrances to patients getting our medications.

Effectively seeking and considering input from patients, caregivers, and frontline healthcare providers is also of concern. The legislation of various DPABs specifies the conflicts of interest that board members cannot have and must disclose. Some even have appointed alternates to allow board members to recuse themselves from making decisions on drugs with which they have financial and ethical conflicts. However, most of the advisory boards are providers, government, and otherwise industry-related. The board members are even required to have advanced degrees and experience in health economics, administration, and more. The majority of the discourse is not weighted towards the patient and our advocates. Few, if any, specific active outreach measures when it comes to seeking patient input. For example, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program requires patient and community engagement outlets in planning activities. But no PDAB legislation, to our knowledge, requires PDABs to engage with these established patient-oriented consortia. We know well in HIV that expecting already burdened patients often struggle to meet limit engagement opportunities from government boards – we know the very best practices are going to patients, rather than expecting patients to come to these boards. Beyond these limited engagement opportunities and failure to reach out to spaces where patients are already engaged, some states have exceptionally short periods in which to gather these inputs.

However, depending on the individual state’s DPAB structure, there is an opportunity for patients, caregivers, and organizations to give input through public comment periods and particular meetings aimed at stakeholder engagement. For states considering PDAB legislation, like Michigan, patients can and should engage in the legislative process. One place to keep abreast of different state’s PDAB activities is the Community Access National Network’s PDAB microsite. The microsite has an interactive map where you can access various states’ PDAB sites as they are created. States with fully formed PDABs have sites that display their scheduled meetings, previous decisions made, agendas for future sessions, and, most notably, details of the process for the public to provide input. Most of the meetings are open to the public, with the public invited to provide oral public comment or to submit written comments. Attending meetings and speaking directly to the boards is a way to have board members and others hear directly from those who will be affected by their decisions. Written public comment is also essential, especially from community patient advocacy organizations. Some DPABS also provide access to virtual meetings where stakeholders can provide feedback and input.

Medicare has six protected drug classes: anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antineoplastics, antipsychotics, antiretrovirals, and immunosuppressants. This means that Medicare Part D formularies must include them but that protection exists because we know how important these medications are. Antiretrovirals and oncology medications are a part of that list because adversely affecting the mechanisms of access to those drug classes is life-threatening to those who need them. It is imperative that continued scrutiny be placed upon DPABs to ensure that their benefits are patient-focused, like reducing administrative burden and barriers to care, rather than a mask that ultimately benefits payers by increasing their profits.

Underprepared: Opioid Settlement Dollars are Coming

The opioid epidemic has ravaged communities across the U.S., resulting in significant settlements from the pharmaceutical industry. However, the allocation of these funds, likely to exceed $50 billion, raises concerns about potential mismanagement.

Past public health crises have led to significant settlements. The 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, for instance, was heralded as a landmark deal. Major tobacco companies agreed to pay billions to 46 U.S. states, funds that were ostensibly earmarked for anti-smoking campaigns and health programs. Yet, as research from RAND later revealed, a significant portion of these funds were diverted to unrelated projects. The promise of a healthier future was overshadowed by the allure of immediate fiscal relief, a misstep that has had lasting implications and begs the question. Will the opioid settlement reach the same result or have states learned their lesson?

Recent Concerns

Probably not, as the misuse of settlement funds remains a concern:

•COVID Funds Misdirection: In a move that sparked controversy, some states opted to use COVID relief funds for prisons, diverting resources from pandemic relief efforts. This decision underscores the tension between immediate fiscal needs and long-term public health goals.

•Mendocino County's Opioid Funds Dilemma: In a decision that drew sharp criticism, especially from those directly affected by the opioid crisis, Mendocino County used over $63,000 of opioid settlement funds to address a budget shortfall, despite having the highest rate of overdose deaths in California.

•New York's Opioid Funds Controversy: Raising eyebrows and questions about the state's priorities, funds intended for opioid crisis mitigation in New York were instead used for overtime expenses related to narcotics investigations.

The Current Landscape

While the anticipated $50 billion from opioid lawsuits offers hope, the lack of standardization and oversight in fund distribution is concerning. The primary objective of these funds is to bolster prevention, treatment, and recovery infrastructure, but it is feared that the absence of clear guidelines and reporting mechanisms will lead to misallocation and abuse. Only 12 states have committed to detailed reporting, emphasizing the need for transparency.

The Profit-Driven Rehab Industry's Ethical Crisis

Challenges posed by the profit-driven rehab industry in the U.S. include aggressive sales techniques, overcharging, and substandard care. The system often pushes vulnerable individuals into treatments that may not be in their best interest. The Affordable Care Act, while praised for mandating private insurance programs to cover addiction treatments, inadvertently led to a surge in for-profit rehab clinics, some of which prioritize profit over patient care, further emphasizing the need for rigorous oversight and quality standards. Few state officials are familiar with these market and health landscape dynamics, meaning few officials are ready to offer the necessary oversight of these dollars and the programs they’ll be going to support. That includes drug court programs.

A recent investigation by Spotlight PA highlighted the lax oversight of addiction treatment facilities in Pennsylvania. The Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs (DDAP) in Pennsylvania has been criticized for allowing providers to continue operating despite repeated violations and harm to clients. The tragic story of Adam Kalinowski, who died less than 24 hours after entering a treatment center known as Addiction Specialists, Inc. (ASI), serves as a poignant example. ASI had a history of violating state rules, and a wrongful death suit against them resulted in a judgment of over $1.6 million in damages.

Drug Courts

In response to surging drug-related criminal cases, drug courts have emerged as a solution, offering offenders a chance at rehabilitation instead of incarceration. However, there are serious vulnerabilities. Recent revelations in Louisiana provide an example of how lax federal oversight of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) grants funding of drug courts have lead to corruption, kickbacks, and questionable practices within these drug court systems and the treatment centers they refer defendants to.

In Lafayette, Louisiana, a mysterious $3 million appropriation for a substance abuse rehab facility became the epicenter of controversy. In the previous year, while the state Senate was formulating the state budget, an unusual amendment was introduced, directing $3 million to a governmental health organization in Lafayette for a 70-bed addiction treatment center. It was later revealed that three businessmen, Mark Fontenot, Jeff Richardson, and Leonard Franques, were advocating for this funding to establish a substance abuse rehabilitation facility in Lafayette. Franques is currently at the heart of an expanding bribery investigation that has implicated officials from the 15th Judicial District Attorney’s office in Lafayette, among others. The scheme involved DA Office kickbacks for steering pretrial diversion defendants to four businesses, including Lake Wellness Center, Franques' outpatient rehab facility.

The scandal in Lafayette highlights the intricate web of connections and potential conflicts of interest surrounding substance abuse rehab facilities, the justice system, and state legislatures who will be in charge of setting appropriations for these historic opioid settlement funds. Harm reduction and Justice advocates will need to work closely together in order to push for necessary “watch dog” activities and opportunities in these referral systems.

The Crisis of Medication Assisted Treatment Access for Minors

The rise of fentanyl has dramatically altered the landscape of opioid addiction. Teenagers are developing severe dependencies at an alarming rate, transitioning rapidly from experimentation to intense dependence. This swift onset of addiction underscores the urgent need for effective treatments tailored to this age group.

Despite the proven efficacy of buprenorphine, considered the gold standard for treating opioid use disorder, less than a quarter of residential treatment centers for adolescents offer it. This lack of access is deeply concerning, especially given the sharp rise in overdose deaths among teenagers, exacerbated by the proliferation of fentanyl.

Several barriers hinder the provision of MAT to minors:

• Philosophical Objections: Some facilities object to medications like buprenorphine on philosophical grounds, despite its proven efficacy.

• Lack of Expertise: Many treatment centers lack the necessary expertise to treat adolescents with MATs.

• Stigma: The stigma associated with MATs, especially among teenagers, poses a significant barrier. If teenagers feel marginalized for taking medication, they might avoid it.

• Systemic Barriers: A shortage of certified providers and underfunded facilities highlight the systemic challenges that need to be addressed to tackle the opioid crisis effectively.

The lack of MAT access for minors raises concerns about the allocation of opioid settlement funds. The funds are intended to address the opioid crisis head-on. If they aren't used to ensure access to MAT for all, including minors, public trust in the system could erode. Furthermore, without access to effective treatments and education, teenagers are at a higher risk of overdose and death. Addressing the barriers to MAT access for teenagers is crucial to ensure that the funds are used effectively and that this vulnerable population receives the care they desperately need.

The Role of the Department of Health and Human Services

The HHS plays a pivotal role in shaping the nation's response to the opioid epidemic. It oversees fund allocation, issues grants to incentivize particular programming, and sets care standards. Ensuring these standards are stringent and patient-centric is vital. State health departments face challenges, including staffing shortages, which can impact fund management.

State Health Department Challenges

State health departments, such as the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS), play a crucial role in addressing the opioid crisis at the local level. However, these departments face significant challenges, including staffing shortages and budget constraints. For instance, the NCDHHS has grappled with a 28% vacancy rate, which has doubled since the onset of COVID. Such staffing shortages can severely hamper the department's ability to manage and allocate funds effectively. These challenges have direct implications for local initiatives, such as the Queen City Harm Reduction's housing pilot program, which faced delays due to funding issues.

Lack of Guidance on Contract Quality with Local Drug Courts

While the HHS provides oversight and sets standards for care, there has been a notable lack of guidance on increasing contract quality between local drug courts, private and publicly funded managed care programs, and providers. Given the potential for conflicts of interest and corruption within the drug court system, as evidenced by the Lafayette bribery scandal, this lack of guidance is concerning. Ensuring transparency, accountability, and quality in contracts is a key factor that will ensure opioid settlement funds are effectively used at every level.

Conclusion and Call to Action

The opioid epidemic presents a monumental public health challenge. The opioid settlement funds offer a unique opportunity to address these interlinked crises. However, without stringent oversight and a clear roadmap, there's a risk that these funds might not be used to their maximum potential.

The rapid allocation of funds without proper oversight is a recipe for disaster. It's crucial to ensure that these funds are channeled into comprehensive programs that not only address OUD but also the associated risks of HIV and HCV infections.